SIR ALEXANDER MURRAY, 3rd Lord Stanhope

Sir Alexander Murray was born about 1687, the son of Sir David Murray, a Jacobite involved in the 1715 rebellion. On his return to Scotland from the ‘foreign university’ at which he had been educated, Sir Alexander married the heiress Grisell Baillie, whose money he was to spend on his activities on the Ardnamurchan Estate. However, Sir Alexander’s marriage had lasted only a few months when his jealous rages resulted in the couple splitting up and, in 1714, formally separating, an event which seems to have unbalanced him still further.

Sir Alexander was elected to parliament for a Peeblesshire constituency in 1710 but did not seek re-election in 1713. He took up arms in the Jacobite rebellion of 1715, was captured at Preston, and languished for some months in prison before his appeals to the Duchess of Marlborough, among others, and his promises of future loyalty to George I secured him the benefit of the indemnity, though for a time he kept up his Jacobite contacts, visiting France in 1718.

Sir David bought the estate in 1722, after which Sir Alexander seems to have turned away from the Jacobite cause, instead throwing himself into another cause – that of economic and agricultural ‘improvement’ in the Highlands. In 1722 he discovered a substantial deposit of lead ore near Strontian which, after his father had passed the Ardnamurchan Estate to him in 1726, he set about exploiting. On finding that the local people lacked necessary skills, he imported English workmen, housing his employees in a village which he called New York. When, despite his efforts and the large sums he invested, the mines proved uneconomic, he leased them to the York Buildings Company.

As far as the agricultural development of Ardnamurchan was concerned, Sir Alexander believed that the best plan was to commence his improvements on the higher land, where the rain fell, and that by leading the water along the hillsides in trenches or canals he could control it. These trenches are still visible today, as can be seen in the above photo.

He was also responsible for draining large areas of the lower ground, activities which are best seen to the northeast of Achnaha, in the area of marshland called Glendrian Moss.

Sir Alexander’s improvements extended to the houses his people lived in. In 1725 he wrote, “….they make a great rout about the trouble & Expence they’l be at in building of Stone houses yet… Stone houses are mostly everywhere Cheaper than the Creel houses. They last much longer, whereby the tennents will be saved of the constant yearly Slavery they are in building New and repairing of the old Creel houses.” AHHA is finding the remains of more and more of these stone houses, typically 7m to 8m long and 4m to 5m wide with rounded corners and a door in the centre of one of the long sides.

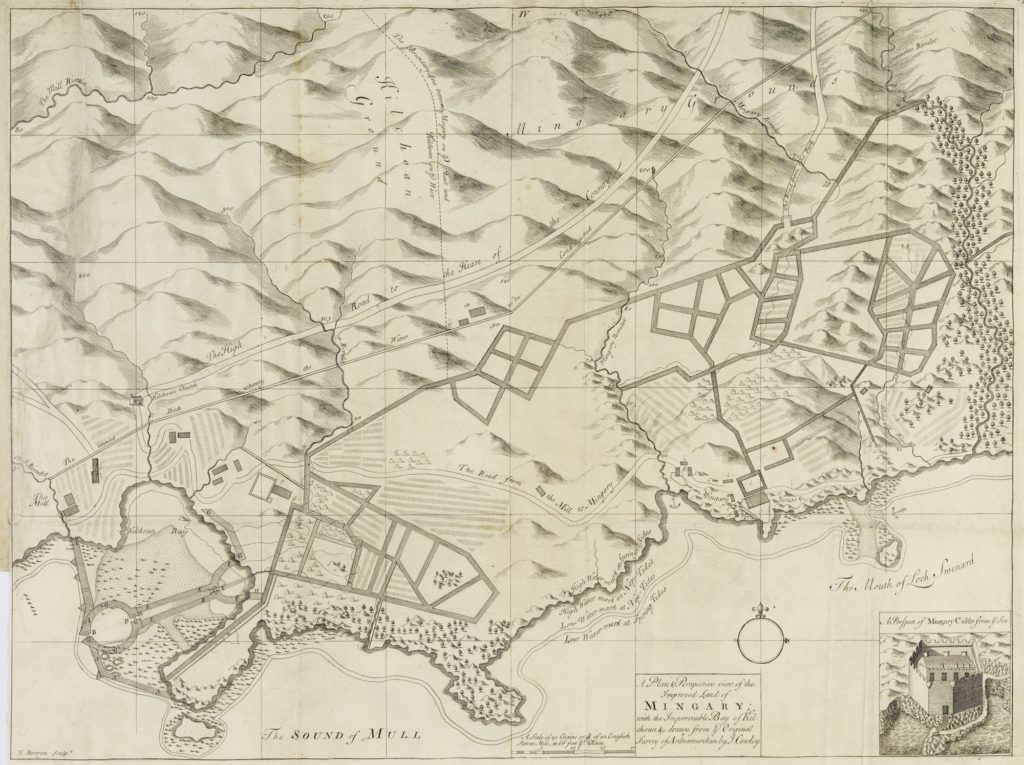

The extent of Sir Alexander’s holdings is shown in this map, drawn by John Cowley and published in 1734. [1]

One of Sir Alexander’s legacies is a map of Kilchoan and Mingary drawn by the cartographer John Cowley, also in 1734, and called ‘A plan and perspective of the improved lands of Mingary’ [1]. Some of the features shown in the map, such as the complex of structures in Kilchoan Bay and the ditch shown running from the Choiremhuilinn burn to the Millburn, could never have been built as there is no evidence of them today, so they may have been projects which Sir Alexander planned. However, there is ample evidence on the ground today of the extensive drainage of the land to the east of Mingary.

The map is also of interest for some of the buildings it shows. Kilchoan has surprisingly few buildings, while the buildings at Mingary suggest that the settlement there still existed at that time. The remains of some of the isolated houses, such as the one half way along the Kilchoan-Mingary track, can still be found today.

Another interesting feature is that the main road out of Kilchoan seems to have started at the north side of St Comghan’s church and run eastwards, some distance to the north of the road today.

Sir Alexander’s hopes for his various schemes came to nothing. By the early 1730s he had, as he put it, ‘sacrificed’ his ‘private fortune’, ‘the money credit of his friends’, and ‘even . . . his private character and constitution’. He was bitterly resentful of what he felt to be sabotage by the agrarian violence of Campbell clansmen.

In 1733, a ruined man, Sir Alexander made over his whole estate to his nephew, Sir David Murray, the son of Sir Alexander’s brother, David Murray.

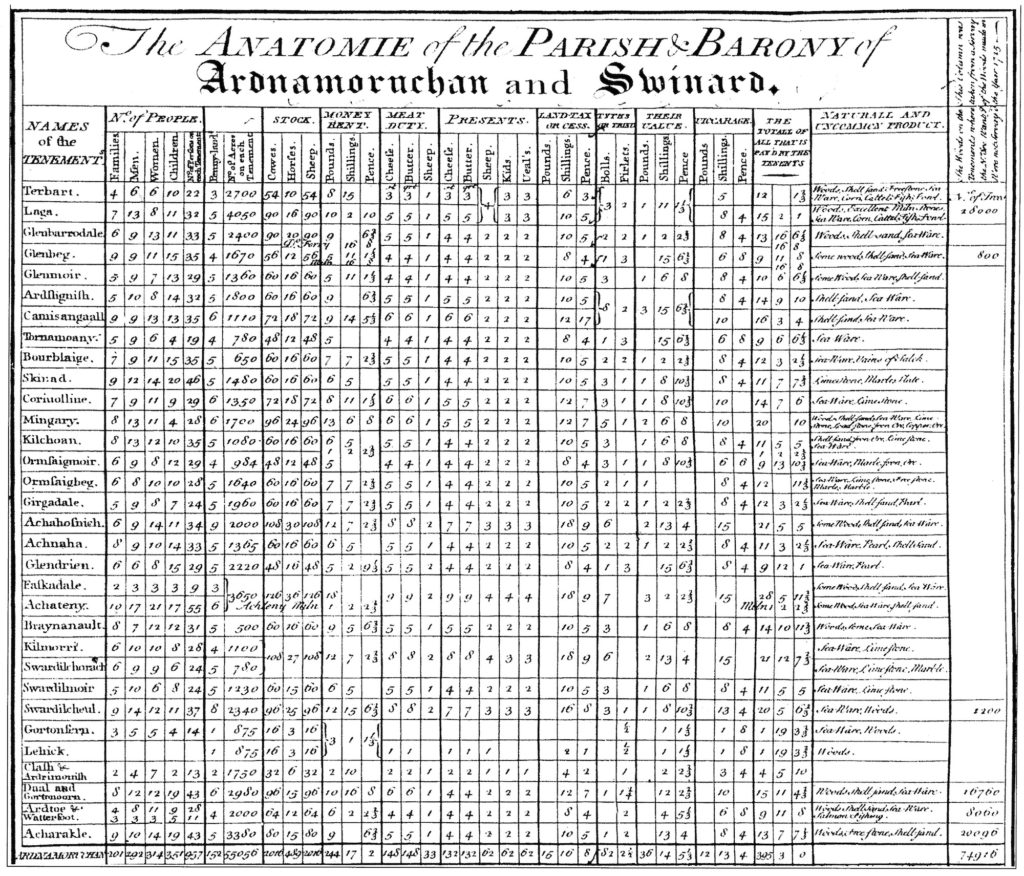

The survey of the estate was completed in 1737 and was published in 1740 in Sir Alexander’s “The True Interest of Great Britain, Ireland and our Plantations”. This consists of a collection of rambling papers on a variety of issues, from the condition of Scotland to farming and irrigation to the need to reform the heritable courts. A digitised version is in the New York Library and can be read here. However, the book does give an invaluable snapshot of the state of the Murrays’ holdings, which included Ardnamurchan and ‘Swinard’ – Sunart. This shows the settlements before the early processes of clearance occurred which resulted in some of the settlements – Camas nan Geall is an example – being depopulated by the end of the 18th century.

Sir David in turn went bankrupt in 1738, and Sir Alexander died in 1743. The Campbells reacquired the estate, so when Bonnie Prince Charlie landed in Moidart in August 1745 at the start of the Jacobite rebellion, Mingary Castle was garrisoned by Donald Campbell of Auchindoun, in his position as the factor of the Duke of Argyll’s Ardnamurchan properties.

In 1767 the estate was sold to James Montgomery but he sold it in the same year to the first of the Riddells.

The RIDDELLS of ARDNAMURCHAN:

The Ardnamurchan Estate, which included the district of Sunart and the Strontian lead mines, was acquired by James Riddell, LL.D., who was created first baronet of Ardnamurchan in September 1778. He had married Mary, daughter and heiress of Thomas Miles of Billockby Hall, Norfolk, by whom he had two sons, both of whom held property in Norfolk.

We have not been able to find much about Sir James’ time on Ardnamurchan, but when he died in 1797 his elder son, Thomas Milles Riddell, had pre-deceased him, so the estate passed to Thomas’ elder son, James Milles Riddell, who became the second baronet. James was born in 1787 and graduated at Christ Church, Oxford. In 1822 he married Mary, youngest daughter of Sir Richard Brooke of Norton Priory, Chester, by whom he had two sons and a daughter. His portrait, left, is in the National Gallery.

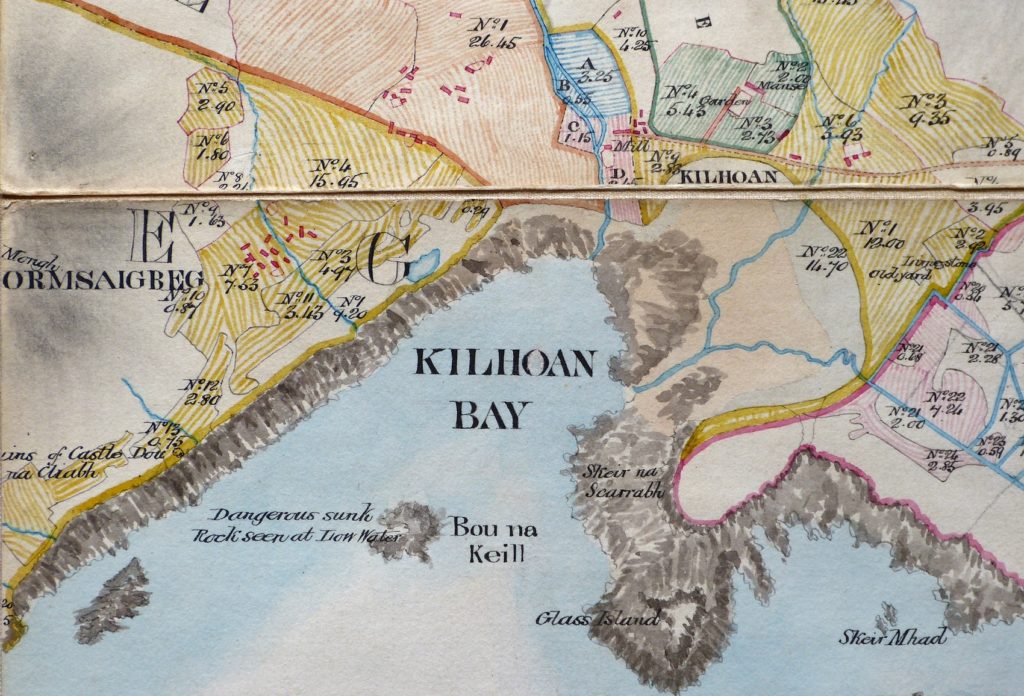

During the first decade of the 19th century, Sir James commissioned the mapmaker William Bald to draw a map of Ardnamurchan. Enititled ‘Ardnamurchan and Sunart the property of Sir James Milles Riddell, Bt.’, it was completed in 1806. The map, drawn on eight panels on a scale of 1:11,600, showed the settlements of Ardnamurchan along with their fields, each one of which was numbered and its area given in acres. This and other information was collated into an accompanying ‘book of reference’.

A digital version of Bald’s map can be seen on the Scotland’s Places website, here, but the original from which it was taken is badly faded. However, a copy, made in 1856, is held by Ardnamurchan Estate, and this shows some of the missing features, such as the buildings. Part of the Kilchoan panel from this map is shown above, courtesy the Ardnamurchan Estate.

That this exercise was part of a response to the Estate’s financial problems is supported by work commissioned in the next year, 1807, from Alexander Low. Entitled ‘Valuation of the Estate of Ardnamurchan and Sunart’, Low, as well as summarising the areas of each township, listed recommendations for the future use of the land. Thus for Tornamona he wrote, “This farm is not very well arranged and should properly be joined to the next [Bourblaige]. Both together would make a good sheep walk fit for Cheviot sheep, but the junction would occasion the removal of a number of poor tenants.”

What followed was the first round of clearances to affect Ardnamurchan Estate. In 1828 the settlements of Camas nan Geall, Tornamona, Bourblaige, Skinnid and Choiremhuilinn were cleared. The first three were joined into a sheep farm which was let to John MacColl, the factor who had been responsible for the clearances, who held the farm until 1833. Skinnid and Choiremhuilinn were added to Mingary, the land subsequently becoming a deer park.

An account written in 1892 describes the Bourblaige clearances as a process “….attended with many acts of heartless cruelty on the part of the laird’s representatives. In one case a half-witted woman who flatly refused to flit, was locked up in her cottage, the door being barricaded on the outside by mason-work. She was visited every morning to see if she had arrived at a tractable frame of mind, but for days she held out. It was not until her slender store of food was exhausted that she ceased to argue with the inevitable and decided to capitulate.” Another observer recorded that, “To clear Bourblaige, the laird’s men shot the dogs, and they shot the goats, and they drove away the cows. And then they took the roofs off. It was in the wintertime that they did it. Ploughs were put through the potato pits so that they would spoil in the frost. And the people walked to Swordle [on the north coast] through showers of snow.”

Not all the families went to one of the three Swordle settlements. Some moved to Ormsaigbeg, Acharacle or Glasgow, and some emigrated.

To add to Sir James Riddell’s problems, the following decades saw periods of famine, particularly in the years 1836-37 and 1846-47. The latter was aggravated by the arrival of the potato blight, which ravaged the crops upon which many of his tenants depended and which continued until 1856. Coinciding with this, the price of black cattle, which were farmed by the small tenants and then driven to market in places like Falkirk, also fell.

In the years after 1843 Sir James also had to contend with the consequences of the Great Disruption, in which the Free Church broke away from the Established Church of Scotland. Free Church congregations in both Kilchoan and Strontian asked for land upon which to build their new churches, and were refused, the Kilchoan congregation having to worship in the open air on the banks of Lochan na Crannaig. An account here describes how the Strontian confrontation ended, and the Kilchoan congregation was also finally given its land.

The second round of clearances took place from 1852 onwards but we know much more of these through the papers of the trustees of Sir James’ estate. By 1838 Riddell’s debts had risen to £52,000 and the estate manager urged that the estate be ‘purged’ of tenants who were of a “delinquent or doubtful character” even though, during the 1830s, 138 tenants had already emigrated. To add to his problems, the condition of the tenants worsened as a result of the potato famine which hit the area in 1846. Sir James pleaded for help for the 3,000 inhabitants on his estate, writing that, “destitution is at our door” and for money for projects such as land reclamation, road building and fishing to help the three hundred men on the estate who could not provide for their families. By 1848 half of the population of the Ardnamurchan district were in receipt of relief.

In the face of his mounting debts Riddell’s creditors agreed that a voluntary trust be set up. The trustee was Henry George Watson, an accountant in Edinburgh, who was conferred with the powers to “output and input tenants” and recover rents. His 1848 report on the state of Riddell’s affairs showed that Riddell’s debts had risen to £95,606, the realisable assets of the estate being a mere £11,856, so the estate had net liabilities of £83,750. The annual income was £7,242 of which £6,497 comprised rents from tenants, while expenditure amounted to £6,151. With an annual allowance of £600 to Sir James, this meant that only £491 was available for financing the whole running of the estate. The continuing ability of his tenants to pay rents was therefore vital, yet over the next three years arrears continued to rise and Sir James was forced to move towards selling the Ardnamurchan part of the estate.

In 1852 Watson’s partner, Thomas Goldie Dickson, travelled to Ardnamurchan and, with the estate factor, set about investigating the circumstances of all the tenants. In his report, which he presented within two months, he wrote that, while the cause of rent arrears was due to the failure of the potato crop in 1846, the decline in cattle prices and the ending of public funding for drainage works, the administration of the estate in recent years had been “lacking in firmness” and referred to “….the aversion on the part of Sir James Riddell to compulsory measures being resorted to against the tenants.”

The biggest problems with arrears were, firstly, among the large number of smaller, joint-tenants and, secondly, because large numbers of cottars – 148 in all – on the estate were not on the rent roll. His report continued, “On the Ardnamurchan Estate it will be observed that the Tenants of the Farms of Swordlemore, Swordlechorach, Swordlechoal and Kilmory are so deeply in arrears that it is absolutely necessary that they be removed and the amount due by them realised by a sale of their stock.” Other tenants, particularly those where the head of the household worked away, should also be dispossessed. The areas thus freed would be turned into sheep walks.

However, Dickson wanted to avoid a public outcry at a time when clearances such as these were liable to be reported in the press, so he identified local industries in which those cleared could be employed – wood cutting, bark processing, fishing, and the lead mines on the estate. The fear of publicity did not prevent some callous acts in the clearances which followed. The sick, blind, infirm, widowed, and others who had suffered famine and stock loss, were subject to eviction, bankruptcy, removal to another part of the estate, or thrown onto the parish. For example, John Henderson of Swordlechoal, who had rent arrears of £23 and stock worth £65, was reported to be dying, yet Goldie recommended to “sequestrate and remove” him. He also made decisions which were not purely economic but which reflected his views of contemporary morality, for example where a tenant was of “intemperate habits” or was “living with a woman not his wife”. In the case of Colin Connell, Ormsaigbeg, it was noted that he “drinks somewhat”. Duncan Henderson, Kilmory, was deemed “a clever man, a little too much so… so must be sequestrated for safety.” On the other hand, those who displayed self help, or were considered by Dickson to be ‘deserving,’ ‘hard working,’ ‘industrious,’ ‘respectable,’ or ‘decent’, tended to receive favourable consideration.

Following Dickson’s report, in 1852 summonses of removal were issued at Tobermory Sheriff Court in the name of Sir James Riddell and his trustees to 102 tenants, while five other tenants were sequestrated. In each of the years 1853 to 1856 three summonses of removal were issued as were eight petitions for sequestration. In 1883 evidence was given to the Napier Commission confirming the removals in Ardnamurchan, especially in ‘the Swordles’. Many of those evicted were relocated “to narrow and small places by the shore; some of them have a cow’s grass, and some are simply cottars.” Those resettled were allocated “poor land at Sanna, at the tip of the Ardnamurchan peninsula.” In 1852 15 families (90 souls) from Riddell’s estate emigrated to Australia under the auspices of the Highlands and Islands Emigration Society, eight of them aboard the ‘Allison’ from Birkenhead to Melbourne on 13 September 1852, while a further four families (23 souls) departed in 1854.

Once the summonses for the removals had been issued in the spring 1852, the trustees petitioned the Court of Session to select parts of the estate which might be sold in order to pay debts of £90,000. In July 1853 the Court determined that Ardnamurchan, valued at £87,000, should be put up for sale. As there was no interest the price was reduced to £82,000 in January 1856. In March 1856 an offer was received from James Dalgliesh, and the sale was ratified by the Court of Session in the same month. [2]

Sir James died in 1861 and his elder son, Sir Thomas Milles Riddell, third baronet, succeeded to what remained of the estate.

[1] Map reproduced by kind permission of the National Library of Scotland.

[2] Much of this information is from a paper by Stephen P Walker.