The old church today is a ruin standing on a low hill overlooking the village of Kilchoan, but for some 700 years it was the main church serving a large area of the Ardnamurchan peninsula.

The original church on this site was dedicated to Saint Comghan (Comgan, Chomhghain), a Leinster prince mentioned in the Irish mythologies who lived in the early part of the 8th century. A Christian, he succeeded his father as chief but was defeated in battle by a coalition of neighbouring, non-Christian tribes. Comghan, his sister Kentigerna, her three sons, including Fillan (Fillin), and seven others were exiled. They settled at Lochalsh in Wester Ross, where Comghan founded a monastery and became its abbot. From Lochalsh, Comghan voyaged around the Highlands and Islands, preaching and establishing churches, fourteen in all, one of them at this site on the south side of Ardnamurchan. When he died, St Fillan buried his remains on Iona, where a church was built over them.

The settlement in which Comghan established his church stood on the north shore of a shallow, southwest-facing bay. The church was built on a low hill at the back of the village. While there are still superb views from the site, the trees down the east side, which are relatively recent, now restrict it in that direction. Having the church must have been important to the inhabitants, because their settlement became known for its church (cille) of Comghan (choan), or Kilchoan.

Little is known about the area during the period from the time of St Comghan until the early 13th century. Ardnamurchan was occupied by the Vikings, whose main contribution was in place names, particularly of coastal features and settlements. However, a Viking boat burial, found at Swordle in 2010 by members of the Ardnamurchan Transitions Project, contained a chief with all his regalia.

Evidence for the original church on the site has been lost. The earliest remains, mainly in the lower parts of the west and east gables, are said by the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS) to be 12th to 13th century. The structure is aligned east-west and measures 14.4m by 5.2m. Although the walls are said to be of differing dates, all are built of random rubble with dressings of greenish-grey sandstone, possibly from Lochaline on Morvern.

We do not know who built the 12/13th century church, but it may have been the MacDougals, who built Mingary Castle some time between 1265 and 1290. They lost Ardnamurchan to the MacDonalds, whose right was confirmed by Robert Bruce after the battle of Bannockburn in 1314. The sept of the MacDonalds which occupied Ardnamurchan from then on was the MacIains, who held the area for some 300 years before losing it to the Campbells. Both MacIains and Campbells would have worshipped in this church.

From 1624 there is a reasonably good record of the ministers who served in this church. The first was Donald Omey, a Celtic Catholic, whose ministry extended from Morar to Kilmallie, its southern border being Loch Sunart. Details of the minsters that followed can be found in the booklet ‘Ardnamurchan – Annals of the Parish’. By this time, the church was referred to inlet as ‘Kilchoan church’.

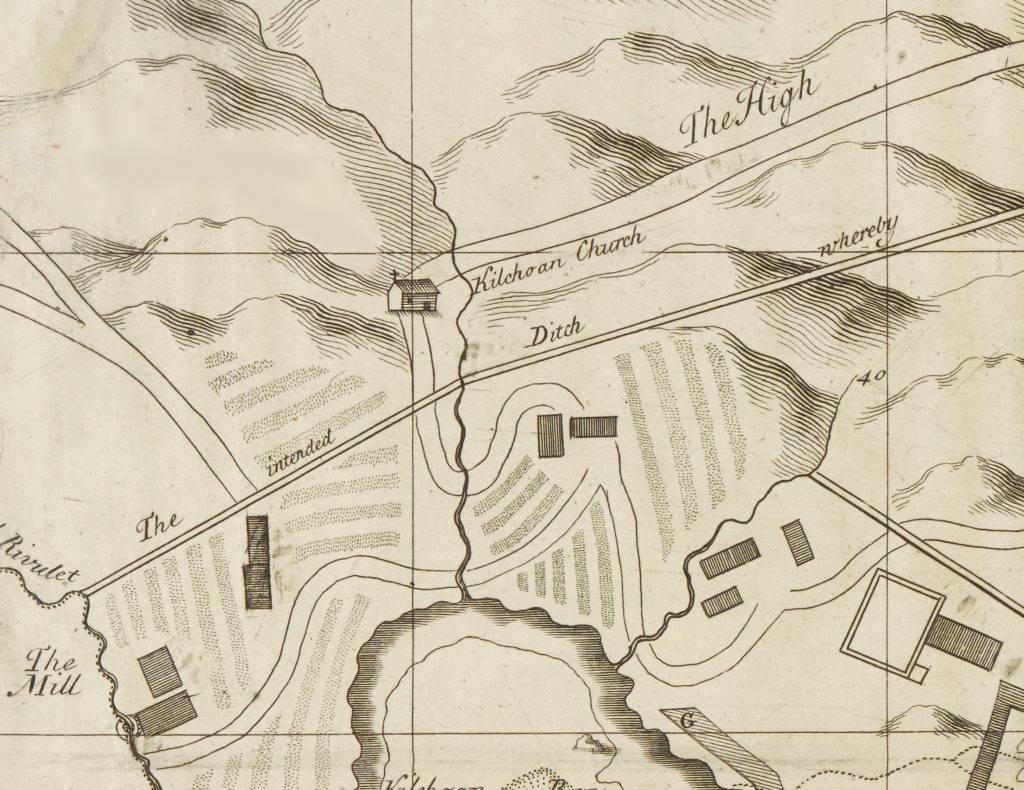

Cowley’s map of Kilchoan, dated 1734, shows the church with a cross above the west gable end and, in the south facade, a door to the east and a single window to the west. It is difficult to know how accurate this is because much of the map seems to have been of the then landlord, Sir Alexander Murray’s rather fanciful schemes, such as his ‘intended ditch’. However, the window in the west gable end, which existed at the time, isn’t shown.

By the mid-eighteenth century the Campbell Dukes of Argyll were choosing the ministers. After a gap of two years, when there was no minister, Kenneth MacCauley was appointed in 1761. Shortly afterwards, the church was renovated, probably in the years 1762-63 – a stone dated 1763 is the keystone of the most easterly of the three arched windows in the south wall. While we do not know who paid for what must have been an expensive project, Ardnamurchan Estate at that time was in the hands of Donald Campbell of Auchindoun, in his position as the factor of the Duke of Argyll’s Ardnamurchan properties. This restoration was either not particularly effective or not maintained as the church was again in a poor condition 50 – 60 years later.

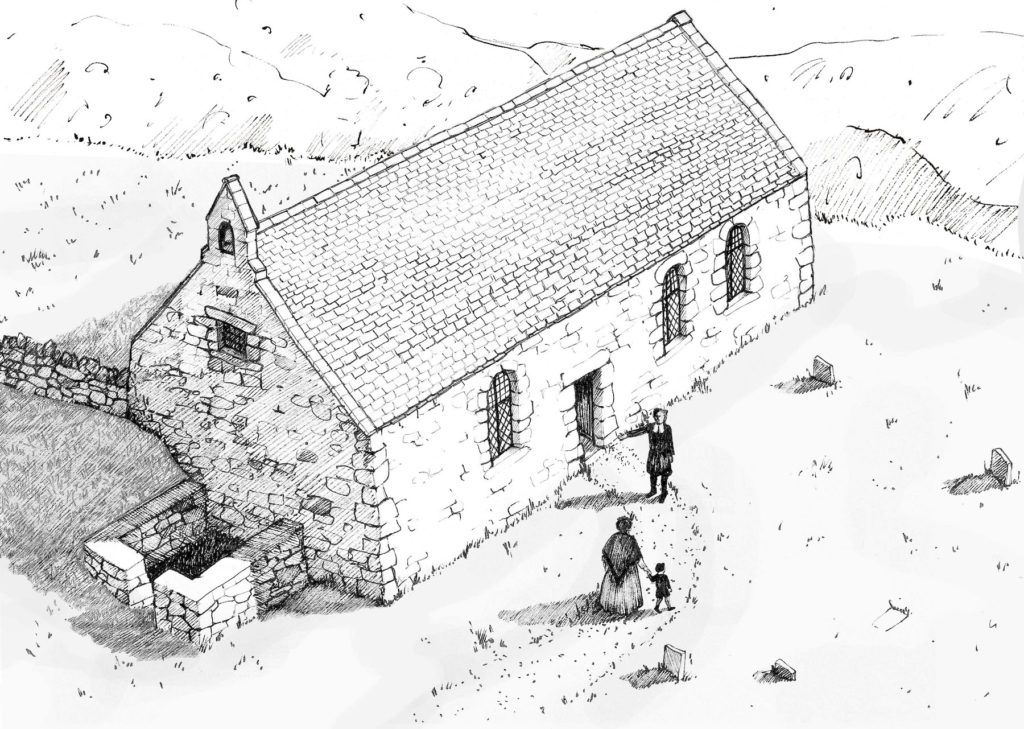

This sketch, by artist Rachael Kidd, shows the church as it might have looked in 1800. The south facade is as we see it today but the west gable end has a ‘bell cot’ and a window. Below it is a burial enclosure. Note that the present ‘new cemetery’ is outside the graveyard wall, and that there are few headstones.

William Bald’s map of Ardnamurchan Estate, drawn in 1806, shows the manse with a walled garden to the south, but does not show the church. While this may mean that the church was already abandoned, a number of ministers followed, with Angus MacLaine appointed by the Duke of Argyll in 1827. By this time the church was in a dilapidated state so a committee, under the then owner of Ardnamurchan Estate, Sir James Milles Riddell, raised the necessary funds and supervised the building of a new parish church. The new church was opened in 1831, at which date the old church was reported to be “long in ruins”. Today, only the walls remain.

SOUTH FACADE:

The RCAHMS report states that the south wall is entirely 18th century. The entrance has a stone slab as a lintel, and the facade includes three arched windows, one to the west of the door, the other two to the east. The key stone at the top of the easternmost arch has 1763 carved into it, the presumed date that the reconstruction was completed. AHHA carried out repairs to the south wall in 2016, which included strengthening the stone door lintel and adding oak lintels behind it, and re-pointing and strengthening the arches and sills.

NORTH FACADE:

The north wall has no windows but once had a door towards its east end. This can be clearly seen from the interior of the church. For reasons that are unclear, the lower part of the door has been blocked in a different way from the upper. The later raising of the burial ground to the north of the church means that only the top of the door can be seen on the outside. According to the RCAHMS, the insertion of this door was carried out in the 18th century restoration, and must later have been blocked.

GALLERIES:

The building, as reconstructed in the 18th century, had galleries at the east and west ends to increase its capacity. The beam sockets which supported these wooden structures can be seen in both the north and south walls. The galleries were reached by internal staircases in the northwest and northeast corners, with the altar and pulpit placed between them against the north wall. A similar arrangement, except with addition of a south gallery, exists in the parish church which replaced St Comghan’s and which is still in use today. One of these galleries was reserved for the laird so it may have been that one of St Comghan’s galleries was for similar use.

WEST GABLE END:

The lower half of the west gable wall has, according to the RCAHMS, “a good deal of medieval masonry”. In it there is a lintelled window which is “deeply splayed” – narrow on the exterior and wide on the interior. While this is blocked, it is suggested that this was not an original medieval window but a later replacement of an original window. As with the north wall door, the RCAHMS suggests that the blocking was done some time after the 18th century.

The upper part of the west gable was reconstructed in the 18th century, and included a stone-lintelled window. This lit the gallery at the west end of the church, probably accessed by stairs which ran along the north wall.

The RCAHMS report states that the west gable is “surmounted by the stump of a plain, rectangular bell cot”, but this is difficult to see today.

Attached to the outside of the west gable is a rectangular walled structure which the RCAHMS describes as a burial enclosure. It does not appear to contain any graves so it has been suggested that coffins may have been placed in it prior to a funeral.

EAST GABLE END:

As with the west gable, the lower part of the east gable is medieval. The centrally-placed window opening at ground floor level, now blocked, retains part of a rebated daylight opening of 12/13th century age, while the upper part of the gable is similar to the west wall, having an 18th century window opening. As with the west gable, there was a gallery at this end of the building.

The exterior of the east gable is difficult to access through dense woodland, but it is worth the effort as some of the features of the original medieval building are visible, including some freestone quoins which form the angles of the walls. They are of a greenish sandstone which is not local.

The Old Cemetery:

The church stands in a large burial ground surrounded by a drystone wall, most of which was probably built or rebuilt during the 1761-63 work on the church. The churchyard today is roughly D-shaped, with a straight NNW-SSE wall along the east side through the east gable end of the church.

The earliest map which depicts the churchyard clearly, the OS 6” map of 1856, shows that the northern part, which contains the more recent graves, was outside the original wall, which cut back from its north side to meet the northwest corner of the church. While the earliest burial in this section is dated 1900, there is good evidence that this area was not enclosed within the wall until some decades later in the 20th century. When this was done, the area was raised by infilling, and levelled. As a result, the lower half of the exterior of the north wall of the church is buried.

The north section (at top left in the following photograph) contains most of the recent burials, in 86 lairs, a record of which is held by Highland Council. This section also includes two servicemen from World War II, whose graves are maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

While over a hundred graves have been identified in the rest of the graveyard, the earliest visible date on a headstone is 1840. However, numerous stones are evidently older, these including one ledger stone with carvings on it which suggest it may date from the middle of the 18th century, and the two Iona slabs from the 14th/15th century. It is also evident from the hummocky ground that hundreds of graves, dug over the centuries, are unmarked.

No local record exists of the burials in the old churchyard, though one must once have existed as some of them are numbered with metal markers.

The MacIain Grave Slabs:

The oldest stones in the graveyard are likely to be the two grave slabs lying just to the southwest of the church door (47 and 48). They are in the style of the Iona School, dating from the 14th or 15th century. Both are badly deteriorated and in need of conservation, but the main carvings are still visible At the top of the one further from the door, which is complete, is a carving of a birlinn, a clinker-built mediaeval ship derived from the Viking longships and the main work boat of the west Highlands. It is one of the symbols of the MacIains of Ardnamurchan, the MacDonald sept which held Ardnamurchan for some 300 years after the Battle of Bannockburn. Below it are some figures which have been described as a ‘hunting scene’, and then a claymore (claidheamh mòr, ‘great sword’ in Gaelic), the Scottish variant of the late medieval two-handed longsword. The characteristic cross hilt with downward-sloping ‘quillons’ is visible. The grave slab nearer the church is broken, its smaller piece having a Celtic design, the larger having a claymore pointing down to a birlinn.

Some Iona grave slabs have writing around the edge, and both these slabs have space there, but their condition is such that, if writing there is, it cannot be read.

There is some question as to whether these grave-slabs were originally prepared for graves in this graveyard or whether they were stolen from Iona and placed there. The Iona Abbey and Clan Donald website tells a story of Mac Iain Ghiorr (1624-94) whose name was proverbial in the West Highlands as a master thief. He was of the “Macdonalds of Mingarry” in Ardnamurchan, “one of the MacIains of Ardnamurchan, a persecuted race” and ” … his new property was Grigadale near Ardnamurchan Point”. The story goes that he brought the two sculptured slabs from Iona to mark his parents’ grave at Kilchoan.

18th Century Ledger Stone:

To the southwest of the church building, lair 71 in the Old Graveyard, is an eighteenth century stone slab, called a ledger stone, carved with a skull and crossbones and a badge. The skull and crossbones was used as a symbol of death, the badge may have been connected to the deceased’s family.

A Schoolmaster’s Grave:

Towards the southeast corner of the Old Graveyard is an obelisk (lair 68) erected to the memory of John McCowan, for many years the Kilchoan parish schoolmaster. The dedication on the main, south face, reads:

Sacred to the memory of John McCowan, Parish Schoolmaster of Ardnamurchan from 1843 – 1874. Died 4 January 1889 aged 80 years. Erected by the people of Ardnamurchan.

During his 45 years residence in the parish of Ardnamurchan, he was loved and respected.

Buried here also is his wife Catherine McCormick who died on the 25 May 1871 aged 51 years.

The east side reads:

Hugh McCowan, their son. Died 20 November 1880(?) aged 30 years and is interred in Glasgow necropolis.

Alexander McCowan, their son. Died at Johannesburg 24 April 1895 aged 39 years.

The west side reads:

Catherine McCowan, their daughter. Died 22 March 1902 aged 42 years. Interred in military cemetery Springfontein.

Research by AHHA members found that Springfontein lay on the railway from Bloemfontein to Cape Town as well as on a line to East London. It had some strategic importance during the Boer War. In March 1900, the British decided to use the town as a base for British troops and, in February 1901, to establish a concentration camp there. A large military hospital under tents was also established near Gibraltar Hill. It is possible that Catherine was a nurse in the camp or the hospital.

The McColl Grave:

To the left of the church door is a large grave (lair 41, Old Graveyard) surrounded by high iron railings. This is said to be the grave of a Mr McColl, the tacksman in the mid-19th century for the then proprietor of Ardnamurchan Estate, Mr Dalgleish. The landlord refused to renew the lease of a tenant farmer in Ormsaigmore because he took up the causes of local farmers, and ordered that the man and his family should be evicted. The tacksman found the eviction difficult and had to send to Oban for soldiers and a court officer to carry it out. As the farmer’s bedridden wife was being carried from the house she cursed the tacksman, saying that when he died no grass would grow on his grave, only dockens and nettles. As can be seen, nothing but weeds grows on it.

The ‘Annals of the Parish’ carries this story, but continues, “In fact, Mr McColl could not have been involved, having died in 1847, years before the incident which is known to have a much more recent dating. The eviction resulted, not from what we might today call militant activism, but from the more mundane fault of failing to pay the rent. While it is true that grass does not grow on the grave that is because of the flat stone, surrounded by iron railings, which covers it.”

The War Graves:

Trooper Norman J King (lair 63, New Graveyard) of the Warwickshire Yeomanry, Royal Armoured Corps, died on July 2, 1940, aged 21 at sea whilst on board the SS Arandora Star. He was a guard sailing from Liverpool to Canada with German and Italian prisoners of war and civilian internees. About 125 miles off the Irish coast the ship was torpedoed by U-47. 13 officers, 42 crewmen, 104 guards, 470 Italians and 243 Germans were lost. Trooper King’s body was washed up on Ardnamurchan.

George MacLennan (lair 16, New Graveyard)was captured near St. Valery-en-Caux where the 51st Highland Division surrendered in 1940, at the fall of France. He was a prisoner-of-war for five years. At the end of the war he was hospitalised first in England and then in Scotland, returning to Kilchoan and Glenborrodale for a few weeks before he died. He was buried on the 11th of November 1946.

The ‘Children’s Graveyard’:

At 65 on the aerial picture is a small depression against the north side of which are several small gravestones, some of slate, and on some of which there are inscriptions. It has been suggested that this may be the burial area for infants and small children.

Burials:

A list of those known to be buried in the churchyard is here.

Acknowledgements:

National Library of Scotland for the clip from John Cowley’s map

‘Annals of the Parish’ published by the Parish of Acharacle and Ardnamurchan

Rachael Kidd for the sketch of the church c1800

RCAHMS at Canmore.org.uk

The Heritage Lottery Fund