Branault, seen here from the south, is a small settlement located near the north coast of West Ardnamurchan. Donald MacDiarmid, in his ‘Ardnamurchan Place Names’ [1], suggests that the name comes from Bra’-nan-allt which, in Gaelic, means the head of the streams.

The Branault standing stone, a scheduled monument, may date back to the Bronze Age. Close beside it, lost in the marsh grass, is another stone, half-buried, which may be the stump of a second megalith, broken off and removed from the site. Many similar standing stones, or megaliths, are associated with the Bronze Age people who inhabited these remote areas of Scotland around 2,000BC, but others may be older, dating to the Neolithic. There are hundreds of Scottish megaliths, many in the Tobermory area just across the Sound of Mull, but relatively few on West Ardnamurchan. The only similar one is at Camas nan Geall, where there is a stone which was later carved with Christian symbols.

The purpose of such stones is unclear. They may have been way markers, memorials to battles or other events, or they may have astronomical significance. One reference suggests the Branault stones have an alignment, with Ben Hiant to the south and the Cuillin Hills to the north – but observation suggests this is unlikely, the stones being aligned roughly 30 degrees to the west of north. Another possibility is that this is a religious site. The stone(s) stand in a dip at the summit of a small, rocky hill, and are surrounded, except on the north, by marshland: it might have been that they stood in the centre of a small pond. The land around the hill is strangely broken, and quite unlike anywhere else on Ardnamurchan. Near them stood a church, Cladh Chatain (the churchyard of St Catan, who died in 710AD). The church and its associated well are now difficult to find, but it wasn’t uncommon for the early Christians to site their places of worship on more ancient ones – as they did with the graveyard at Camas nan Geall.

The earliest written record of the settlement is for 1667, when it was called ‘Branalt’ and was valued at 2 merk land. [2]

In Sir Alexander Murray’s ‘Anatomie of the Parish and Barony of Ardnamurchan and Swinard’, 1727, the settlement was listed as Braynanault and valued at 5 penny land, with a population of 8 families – 7 men, 12 women and 12 children, total 31. The ‘tenements’ covered 500 acres, small compared to other settlements, and the population were allowed to graze up to 60 cows, 16 horses and 60 sheep – the so-called ‘souming’. Under the heading of ‘Natural and Uncommon Product’, Sir Alexander listed wood and ‘sea ware’ – seaweed used for fertilizer. Its rental value was £9 5s 6p.

In 1732 Branault’s tenants were John McLachlan, Archibald McEachern and Duncan McLachlan, while in 1739 the only one named is Allan Stewart. [2]

William Roy’s military map, surveyed some time in the 1750s, marks ‘Braeinald’ as a small, compact group of buildings. [5]

In the Ardamurchan Estate description on the eve of its sale in 1767 it is listed thus: “About a mile & a half above which (Achateny) in a glen lies Brownhault in which there are a good many houses & in tolerable repair being built with Stone and Feal, surrounded with about 20 acres of arable & grass ground, & above it about ½ a mile in the glen about 20 acre more of Haughs, & above them on the Brow of the Hill a large quantity of Scrubb Birch. The Glen fine for pasture & of a great extent.” [‘feal’ is thick turfs used for walls, with thinner turfs were used on roofs, while a ‘haugh’ is a low-lying meadow in a river valley.] [2]

Bald’s map of 1806 marks both the arable fields, in a distinctive colour for that settlement, and the extent of the common grazings, which ran south as far as Loch Mudle and north to the sea at Kilmory Bay. This extract is taken from a faithful 1856 copy of Bald’s map in the hands of Ardnamurchan Estate [3] which shows the buildings in detail. From it we can tell where Branault settlement was, its exact location helped by two small burns, tributaries of the Achateny Water (Avhin Achateny, Bald called it), which curve round the marked site of the settlement, and still exist today. So the sixteen buildings of ‘Braninault’ were grouped around the present Branault House, and it was a typical nucleated settlement with an enclosure.

This photo therefore shows the site of the Branault settlement, with Branault House on the left and some byres to the right which are currently used by Ardnamurchan Estate. Note the ‘lazy beds’ on the hill above.

This photo therefore shows the site of the Branault settlement, with Branault House on the left and some byres to the right which are currently used by Ardnamurchan Estate. Note the ‘lazy beds’ on the hill above.

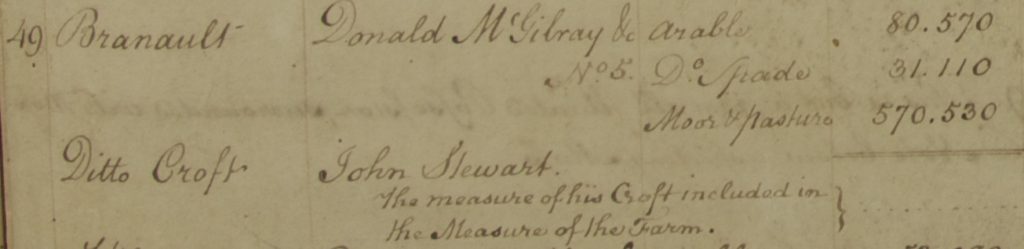

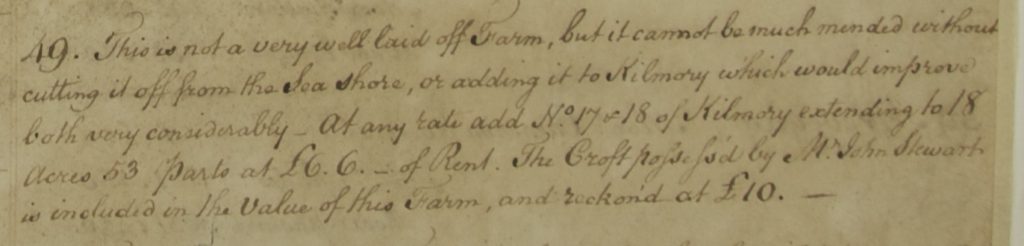

In 1807 Alexander Low produced a report [5] for the then owner of Ardnamurchan Estate, Sir James Riddell, using the information from Bald’s survey to make recommendations as to how the Estate could be reorganised to prevent impending bankruptcy. He listed the principle tenant as Donald McGilbray, and referred to his holding as a ‘farm’. McGilbray was probably the tacksman who was responsible for collecting and paying the settlement’s annual rents. Low separated out a John Stewart, whom he described as having a ‘croft’. The settlement’s 682.21 acres were made up of 80.57 arable, 31.11 cultivated with the spade and 570.53 moor and pasture.

In 1807 Alexander Low produced a report [5] for the then owner of Ardnamurchan Estate, Sir James Riddell, using the information from Bald’s survey to make recommendations as to how the Estate could be reorganised to prevent impending bankruptcy. He listed the principle tenant as Donald McGilbray, and referred to his holding as a ‘farm’. McGilbray was probably the tacksman who was responsible for collecting and paying the settlement’s annual rents. Low separated out a John Stewart, whom he described as having a ‘croft’. The settlement’s 682.21 acres were made up of 80.57 arable, 31.11 cultivated with the spade and 570.53 moor and pasture.

Low recommended that Branault could be ‘mended’ by amalgamating it with Kilmory, something which did not happen.

Low recommended that Branault could be ‘mended’ by amalgamating it with Kilmory, something which did not happen.

In 1827 the land was let to 8 tenants on a year to year basis [2]

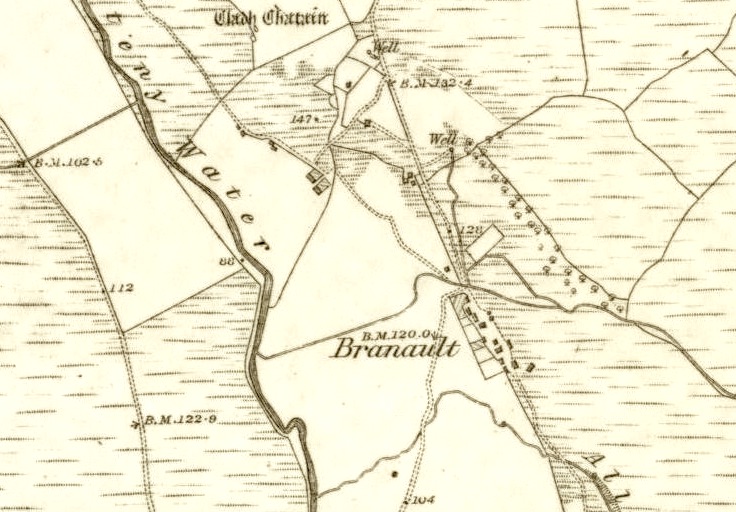

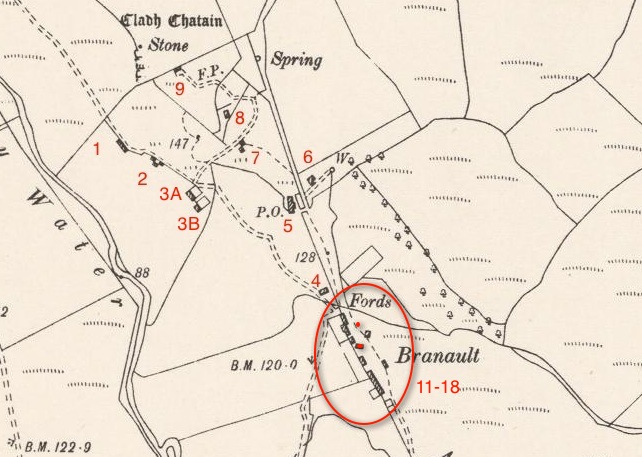

The Ordnance Survey’s 1856 First Series map [5] shows considerable change. The nucleated settlement has gone, and the buildings are now in a linear arrangement along the trackways. The three buildings marked in the red oval are not part of Branault – they are cottars cottages associated with Achateny Farm. So Branault consisted of nine or ten buildings, of which only five were on the old settlement site. This is good evidence that the settlement has been reorganised into a crofting township, with the communally-held settlement inbye divided up between the crofters. The Bronze Age standing stones at Cladh Chatain are marked.

The Ordnance Survey’s 1856 First Series map [5] shows considerable change. The nucleated settlement has gone, and the buildings are now in a linear arrangement along the trackways. The three buildings marked in the red oval are not part of Branault – they are cottars cottages associated with Achateny Farm. So Branault consisted of nine or ten buildings, of which only five were on the old settlement site. This is good evidence that the settlement has been reorganised into a crofting township, with the communally-held settlement inbye divided up between the crofters. The Bronze Age standing stones at Cladh Chatain are marked.

The OS 6″ map of 1872 [5] shows an increase in the number of buildings. These are probably agricultural buildings since all are close to the buildings of the 1856 map. What is clear from this map is how little improved land there is for the crofters’ use – much of the land within the township is marked as rough grazing. The township had two wells. The 1897 OS 6″ map shows little change except that some buildings have gone while others have been extended, and one of the houses serves as a Post Office. The Post Office used to be in Achateny so, although it was relocated to Branault, it continued to be known as Achateny Post Office. Later, it moved to Kilmory, but its name still didn’t change.

The OS 6″ map of 1872 [5] shows an increase in the number of buildings. These are probably agricultural buildings since all are close to the buildings of the 1856 map. What is clear from this map is how little improved land there is for the crofters’ use – much of the land within the township is marked as rough grazing. The township had two wells. The 1897 OS 6″ map shows little change except that some buildings have gone while others have been extended, and one of the houses serves as a Post Office. The Post Office used to be in Achateny so, although it was relocated to Branault, it continued to be known as Achateny Post Office. Later, it moved to Kilmory, but its name still didn’t change.

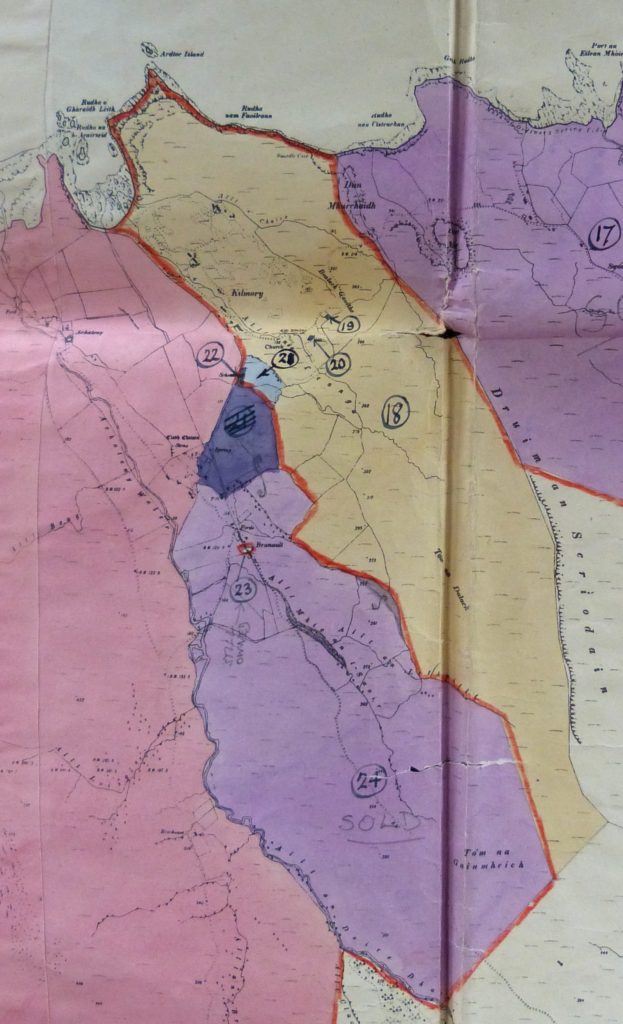

In 1948 much of Ardnamurchan Estate was parcelled up and sold off. This map was published for the sale [3]. Branault, marked in pale purple, lost its corridor to the sea and the area of common grazing which extended south towards Loch Mudle. However, it gained land running down to the Achateny Water which had been part of Achateny Farm, although this did not include the four cottars’ cottages. It also lost an area marked in dark blue which, today, has a number of houses on it. Note however that a small parcel of land, highlighted in red, is marked in pencil as ‘Still Owned’: this is Branault House which was retained by Ardnamurchan Estate and is now a letting house.

In 1948 much of Ardnamurchan Estate was parcelled up and sold off. This map was published for the sale [3]. Branault, marked in pale purple, lost its corridor to the sea and the area of common grazing which extended south towards Loch Mudle. However, it gained land running down to the Achateny Water which had been part of Achateny Farm, although this did not include the four cottars’ cottages. It also lost an area marked in dark blue which, today, has a number of houses on it. Note however that a small parcel of land, highlighted in red, is marked in pencil as ‘Still Owned’: this is Branault House which was retained by Ardnamurchan Estate and is now a letting house.

It is interesting to look back at the 1897 OS map [5] and identify which buildings remain today. 1, 2, 3A and 3B are all ruined, the remains of the cottars’ cottages on Achateny Farm land. 4, which was once a house, is also now a ruin. 5, the old Post Office, is the house called Braeriach. 7 was a house but is now a ruin. 8 is a farm house, and 9 the farm’s byre, though it was once a house.

It is interesting to look back at the 1897 OS map [5] and identify which buildings remain today. 1, 2, 3A and 3B are all ruined, the remains of the cottars’ cottages on Achateny Farm land. 4, which was once a house, is also now a ruin. 5, the old Post Office, is the house called Braeriach. 7 was a house but is now a ruin. 8 is a farm house, and 9 the farm’s byre, though it was once a house.

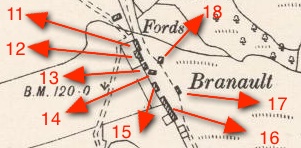

Buildings 11 to 14 have now gone. 15 is Branault House, and 16 has been split into the two buildings that are now byres. 17 and 18 have also gone.

Buildings 11 to 14 have now gone. 15 is Branault House, and 16 has been split into the two buildings that are now byres. 17 and 18 have also gone.

Many thanks to Hughie and Bridget Cameron for their help.