The Change to Crofts:

Starting in 1828, with the clearing of Camas nan Geall, Tornamona, Bourblaige, Skinnid and Coire Mhuilinn, James Milles Riddell, the then-owner of Ardnamurchan Estate, began removing his tenants either to existing settlement lands, such as the three Swordles, Kilmory and Ormsaigbeg, or to newly-designated settlement sites, such as Sanna. Wherever they were moved, the lands of these settlements were reorganised so that, instead of the inbye land being held communally and the fields rotated between different tenants, the inbye was divided into crofts, each croft being held by an individual tenant. In some places, such as Achnaha, the crofters’ houses were left in the traditional nucleated arrangement, surrounded by their fields, as they had been when they were settlements. In others, such as Ormsaigbeg, the old settlement buildings were destroyed and the tenants required to build new houses on their croft land. In every case, the crofting township, as the settlement was termed, retained the common grazings of the old settlement, with each croft having a ‘souming’ – a right to graze a fixed number of cattle and sheep on the common grazings.

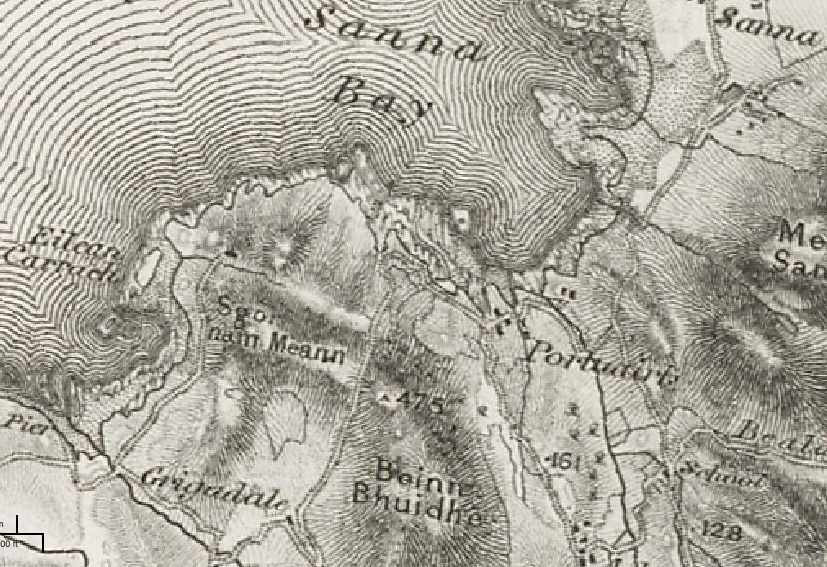

When, in the early 1850s, the three Swordles were also cleared, the pressure on land became even greater, and areas which were increasingly unsuitable for arable farming were pressed into use. Thus Portuairk which, along with Sanna, had been part of Achosnich common grazings, was designated as a crofting township, and people settled there as the Swordles were cleared. The 1856 Ordnance Survey map of the area, above [1], shows the first buildings at Portuairk, many of which still exist on the ground today. They were small, temporary abodes inhabited while the new croft houses were being built.

When, in the early 1850s, the three Swordles were also cleared, the pressure on land became even greater, and areas which were increasingly unsuitable for arable farming were pressed into use. Thus Portuairk which, along with Sanna, had been part of Achosnich common grazings, was designated as a crofting township, and people settled there as the Swordles were cleared. The 1856 Ordnance Survey map of the area, above [1], shows the first buildings at Portuairk, many of which still exist on the ground today. They were small, temporary abodes inhabited while the new croft houses were being built.

With the shortage of land upon which to settle people, all crofts were necessarily small. Some people say, with justification, that the crofts were deliberately kept small so that the occupants would have to work for the Estate to raise the money for their rent. Certainly, many people left Ardnamurchan for periods of the year to work, for example, in the police force in Glasgow or in the British merchant navy.

Some idea of what the croft houses looked like can be obtained from old photographs. This picture of Achosnich, one of the settlements which retained its nucleated structure, is from the collection held by Dorothy Parker, nee Coltart. Some of the older houses, like the one at the right, were single-storey, hip-roofed, thatched, with two rooms each of which had a fireplace, the smoke being led out at the centre of the roof. Newer houses, like the one at top left, were gable-ended, and had their fires, and the chimneys, against the gable.

As time went on, the thatch was replaced by corrugated iron; later still, an upper storey was often added, this in the 1930s, and the roof covered with slates or asbestos tiles. Many of these croft houses, such as these two in Ormsaigbeg, are still in use.

Crofting:

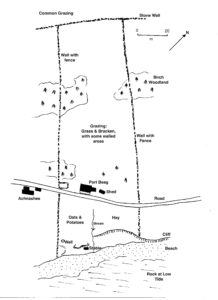

Mary MacGillivray, who was born and brought up on Ormsaigbeg’s Croft 55, gave an account of life on a typical croft in the 1930s. The family croft ran from the Ormsaigbeg common grazings on the lower slopes of Druim na Gearr Leacainn to the shores of the Sound of Mull. Its house, Port Beag, which faced southeastwards, was in the middle of the croft land, and the Ormsaigbeg road passed right in front of it, separated from it by a small flower garden and low wall. To the east of the house stood a byre with a hen house and, separate from that, a hay shed. To the west of the house was a grassy ‘washing green’ where there were lines for drying the clothes. Beyond that was a small walled garden in which Mary’s mother grew blackcurrants, gooseberries and raspberries. To protect the plants from rats, they were surrounded by broken jam jars. There was a gate from the garden onto the road. An 8ft high straw stack also stood in the garden.

The croft was separated from the common grazings by a drystone wall, and from the crofts on either side by stone walls and fences. In the area above our house the family kept two cows on land that was largely grass, heather and bracken. In the summer they were out all night but in the winter they spent the night in the byre. The cows were called down to the byre every day for milking, where they were given some hay. Mary’s mother did the milking but if she was away one of her daughters had to do it. They didn’t like the job as the cows kicked us, though it helped if we tied the beast’s tail to its leg. Each year the cows were dried off before being taken to the bull. During this time, a month or so, we had an arrangement that milk would be available from a neighbour.

The cows were taken to the bull when they came into season in early spring. The bull came from an agricultural centre and was provided free. He was kept on a neighbouring croft. The bull spent the night in their shed but, each morning, the crofter took him up to the field above the road. The rest of the township’s crofts helped by taking turns in feeding him. Mary and her sisters were very frightened of the bull so, when they carried our hay along, we asked the crofter to take it into the field.

When the cows calved, which happened in the byre, the calf was kept in a pen in the hay shed. Each day when it was in use, the byre had to be mucked out by one of the children, the manure being taken across the road and dumped at the top of the lower field.

Croft 55 about twenty blackface sheep on the common grazings at the back of the croft, where they ran with a couple of hundred others. Their sheep could be distinguished by the cuts made on their ears, though the new-born lambs were marked with dye. The sheep did come down onto the croft, when they grazed both above and below the road, but this wasn’t strictly allowed as Ormsaigbeg is a ‘closed’ township, which meant that animals, with the exception of the milking cows, should be kept off the croft land. The township had a tup which ran with the ewes. When they came to lamb, the ewes were left to their own devices. The lambs were sold through auctioneers who came to Kilchoan, and went out by boat from the jetty below the Ferry Stores. Mary’s family never ate lamb: it was too valuable as a cash earner.

They kept between ten and sixteen hens and one or two cockerels, all black leghorn. They spent their day in the field below the road, going as far as the beach, but were kept in a shed on the end of the byre at night. They provided eggs and meat for the pot, but some were sent, live, to relatives in Glasgow as Christmas presents. To do this, we tied their legs with an address label attached, and took them to the post office. The hen house also had to be cleaned out, and that was thrown, with the cow manure, onto the other side of the road.

The family grew potatoes, oats and hay on the gently sloping field below the road, potatoes in the western part, then the oats, and, across the little burn, the hay. The crop land was prepared each year by spreading the manure from the cows and hens, then adding seaweed from the beach, which was hard work. The field was ploughed by two big Clydesdale horses using their our own plough, and then harrowed. The horses were brought over from Achosnich by Neil Cameron, and he was paid cash for his work. My mother fed him a lunch of herring and golden wonder potatoes. Although Neil walked home for the night, the horses stayed and were fed by us, before being moved on to another croft next day.

The middle part of the field was put down to potatoes, mostly Kerrs Pink. After the horses had ploughed the land, the whole family walked behind them pushing the seed potatoes into the soil. Mostly, the seed potatoes were ones they had kept from the previous year but her father did buy some in. After the harvest, the potatoes were placed in a pit for keeping. The pit was in the middle of the potato field, about 4ft in diameter and 4ft deep, and lined with bracken. It held enough potatoes to keep us for a year. Some of the potatoes became rotten as a result of the blight but we cooked and fed them to the chickens.

The seed for the oats was scattered by hand by Mary’s father, who kept the seed corn in a canvas bag and broadcast. It didn’t require any cultivation or further fertilizer. When it was cut the children made stooks which were piled into a straw stack. The straw was used to bed the cows in the byre but, before it was given to them, the grain was stripped off for the chickens. Bracken was cut for bedding for the cattle. Some grain was stored in a cupboard in the house and was used to feed the cows.

The hay was cut using a scythe with the children following behind to pick out the ‘black men’ from the hay before it could be gathered and carried up to the shed. Picking out the ‘black men’, a plant related to the thistle, was a job we hated but it had to be done as it was bad for the animals to eat.

Their horse was kept in a small bothy just above the beach, and it was the children’s job to put the horse into its stable each evening with some hay.

At the western end of the beach, pulled above the tide line, Mary’s father kept his boat. He won a silver trophy in the 1900 regatta in her, but her main use was for fishing. With a friend, he went out after cod, which they sold to the Fascadale fisheries. They were kept in the ice house, which is now the toilet block between the Ferry Stores and the Ferry House. It was easy to catch fish: Mary’s mother would put on some potatoes to cook and ask her father to go out and catch some, which didn’t take long. If he didn’t go out in the boat, he used a rod and line which he cast off the beach below our house. He caught herring, mackerel and cuddies (saithe). [2]

[1] Map courtesy ‘A Vision of Britain’ – here.

[2] Mary’s booklet, ‘Growing Up on an Ormsaigbeg Croft’, from which this account is taken, is available here.