The sites have been backfilled, the finds logged and recorded, the trowels and buckets cleaned, and the stunning and atmospheric Camas nan Geall has been left as it was found, just before we all started on our archaeological adventure in the third week of April. The dig forms part of the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and Historic Environment Scotland (HES) supported Adopt-a-Monument in Ardnamurchan programme, delivered by AHHA and Archaeology Scotland.

As usual, our volunteers have included a wide range of people – from seasoned regulars who reside locally, to very keen novices from further south, who are keen to return to continue the Camas nan Geall community archaeology journey. All were in the capable and highly experienced hands of Ian Hill, Paul Murtaugh and Kieran Manchip of Archaeology Scotland.

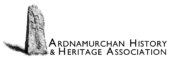

Following the investigation of the 19th century sheep farm tenant’s dwelling, close to the bay last year, we decided to go back in time and set out further up the hill to the northwest of the bay to look at what appeared to be 18th century pre-clearance houses. What is interesting about these structures is they don’t appear on either the Ordnance Survey map of 1875, or Roy’s mid-18th century military map, which is a clear indication that they were never ‘improved’ or built upon, so provide a clear snapshot of the landscape just before the highland clearances.

Two sites were looked at; the first focussed on two neighbouring, very dilapidated structures about a five minute walk from the main track heading north-west. The second contained one structure much closer to the track, hiding under extensive vegetation of bracken and brambles and with a number of curious features that suggested it might be a bit more significant than a simple dwelling.

Site one

Thankfully, the ground cover around the first site was light, mainly because of the time of year. What remained of the walls of both structures was just covered in the usual array of moss and lichen so with the sun shining, and the bluest of skies reflecting on the glittering sea in the bay below, Paul got started on measuring up the proposed trench in the first building.

on measuring up the proposed trench in the first building.

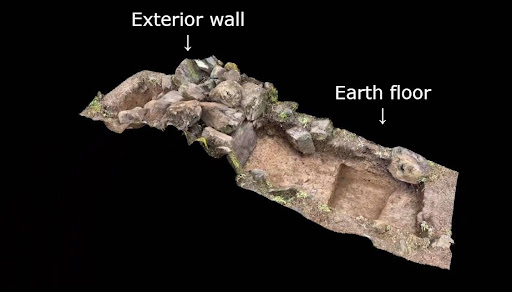

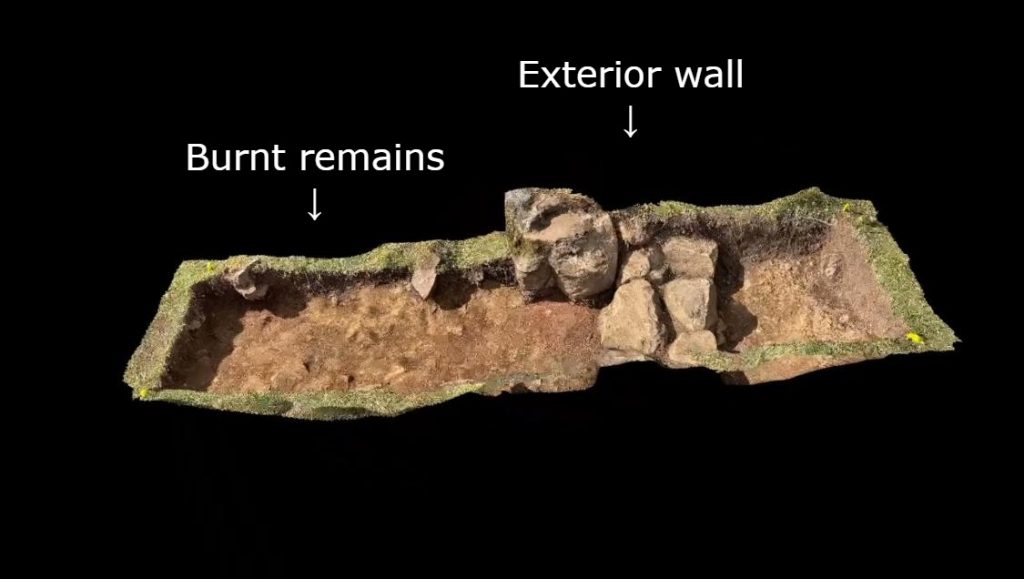

A trench measuring approximately 4 metres by 1 metre was excavated through what remained of the exterior wall on the north side of the building. After painstaking work and the clearing of some significant boulders and stones, the original earth floor of the building was reached.

Red-ish soil deposits at the bottom of the trench revealed a lot of burnt material, which suggested vegetation around the site had been cleared and then burned, and then the house built directly on top of the subsoil.

In terms of finds, it was difficult to try to contain the excitement when two of our regular volunteers, Dale and Ricky, found a musket ball and some smaller shot. Images of the finds were sent to Tony Pollard, Battlefield Archaeology expert (and one of the Two Men (formally) in a Trench).  He suggested it might be buckshot – a type that was used extensively in the American War of Independence. This places the finds at approx 1770, which means this buckshot was fired about 250 years ago.

He suggested it might be buckshot – a type that was used extensively in the American War of Independence. This places the finds at approx 1770, which means this buckshot was fired about 250 years ago.

It’s easy to let your imagination run away with you when discovering finds like this, with images of long-forgotten battlefields playing in your head. The chances are, of course, is that the buckshot was used for hunting game, and the only act of hostility was aimed at a rabbit or a pheasant.

Other finds included bits of clay pipes, ceramics and glass – all typical of the period.

Thanks to the wonders of modern technology, a 3D model was created of the trench which you can see below.

Kieran was overseeing the investigation at the second dwelling a few metres up the hill. It was a similar size and in a similar condition to the first building, deteriorated, lots of tumble, but equally easy to access, given it was April and the bracken was still dormant.

After measuring up the site, a similar trench was dug – through the centre of the outer wall and ending in the interior of the structure. About half a metre down – right in the middle of the dwelling – a hearth was discovered. This is a typical feature of the blackhouse, a building common throughout the Highlands and Islands, largely built in the time between the Clearances and the Crofting Act of 1886. Blackhouses had no chimney and the smoke from the fire would just rise up from the central hearth through the rafters.

Samples from both sites were taken for environmental data processing, so we look forward to discovering exactly what they were burning, cooking – and also growing.

Site two

Further down the hill, Ian was managing the excavation of the ‘mystery building’.

The structure had been surveyed and recorded several years ago by some of the members of AHHA. Initial investigation suggested there was a possibility that the structure might be a church or chapel. Although there was no overwhelming evidence, there were a few key reasons for this theory; it’s of a significant size – much bigger than any of the structures on site one, it’s aligned east to west (a key hint at church architecture), it’s also elevated and quite central to the bay (there are good views over to Baliscate, the early Christian chapel on Mull discovered by the Time Team in 2009).

So, after the spilling of much blood, sweat and tears clearing the site from the bracken and brambles that had provided a very good job of hiding the structure from view, Ian and a few volunteers got to work and dug a trench, also east to west through the exterior western wall, to investigate a) how thick the walls were and b) whether there was a built floor, which would give credence to the church theory.

The hope was to find some floor deposits or perhaps a built floor – laid stones, cobbles or flagstones – but when the floor level was reached, which was significantly damaged by very pervasive bracken roots – it was of a simple beaten earth type. There was also quite a bit of rock incorporated – including boulders of a significant size – which was just ‘hillwash’, rockfall that had tumbled down from the hill behind the building, possibly when the road was built.

In the trench at the far side of the outside wall – which appeared to be just under a metre thick – there were also several large heavy stones, made up of tumble from the significant collapse of the wall, along with more hillwash, which begs the question: Was the building abandoned because of the huge rocks tumbling down on top if it?

The answer is: probably not. The excavations suggested that first, the building was abandoned, then the walls started collapsing and later, the large stones came tumbling down on top of it, so it was highly unlikely that the inhabitants had to flee carrying all their worldly goods on their backs as rocks rained down on them.

So, in conclusion, the mystery building is likely to be another domestic structure at least 200 years old (but of a significant size), and part of the local settlement.