The name Swordle is Norse, Suardail, perhaps derived from the words sward, meaning grassy land, and dahl, field. [1] However, the history of this beautiful valley and bay on West Ardnamurchan’s north coast is far older than the Vikings, and we know much about that early history through the work of the Ardnamurchan Transitions Project, a group of archaeologists who have been excavating in the area since 2006.

The oldest structure they have identified is Cladh Aindreis, a cairn which is dated to the Neolithic, around 6,000 years ago. It originally consisted of a small hole in the ground into which were placed pieces of charcoal and bone. Later, on top of this, a stone cist or burial tomb was built which also contained some bone, and this cist was then covered with a circular mound of stones. The structure was subsequently altered several times, the finds of Beaker pottery indicating that it was still in use during the Bronze age.

Within a few metres of Cladh Aindris is another cairn. Called Ricky’s Cairn, it is a Bronze Age kerb cairn consisting of a ring of stones about 7m in diametre within which is a cist grave, the area within the stone ring being later filled with pieces of rock. Finds of jet beads, probably from North Yorkshire, and other evidence suggest an age of about 1,800BC.

A kilometre to the east of the Swordle valley lies a north-south ridge called Dun Mhurchaidh whose northern end reaches the sea. While this was originally considered to be an Iron Age promontory fort, excavations in 2010 and 2011 have found evidence of burning and of metal working on what may be a ritual site. In addition, pieces of jewelry have been discovered. The site is tentatively dated at around 200BC.

In 2011 the Ardnamurchan Transitions Project archaeologists found a complete Viking boat burial. The boat had been dragged up the beach and placed in an elongate pit. Into this boat a Viking warrior, complete with shield, sword, spear, drinking horn and bronze ring pin, had been laid, the whole then covered in a mound of earth. Although only a few pieces of bone and two teeth were found, this is a wonderful discovery, the first Viking boat burial on the mainland of Scotland. The grave is dated to around 900AD, and its presence is taken to mean that there was a Viking settlement at Swordle, although no further evidence of this has yet been found.

In the years that followed, the land in the Swordle valley was divided into three settlements, Swordlechorrach, Swordlemore and Swordlecheil. It is not clear when they were established, but in 1618, Swordle Chorrach is mentioned in the Register of the Privy Council XII as having two tenants, Donald Roy McTaves [or McAngus] and Rorye McGillimichaell.[2]

By 1667 [2], when the lands were valued, Swordlechorrach is recorded as a 2½ merk land and Swordlemore also a 2½ merk land, but Swordlecheil is still not mentioned.

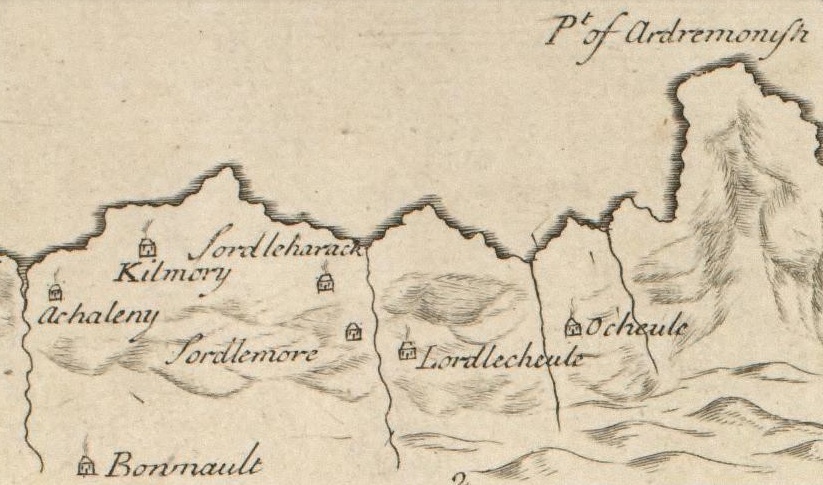

By 1706, the date of Alexander Bruce’s map [3], the three settlements were in existence, marked as ‘Sordleharack’, ‘Sordlemore’ and ‘Lordlecheule’.

Following the 1715 rebellion, a record was made of the men who handed in their arms at an amnesty at Mingary Castle. Only ‘Suaradilechoill’ is mentioned, and from there six rebels are listed, Duncan Stewart, Duncan McIlleise, Donald McColl, John McCraiggan, Duncan McIllom and Angus Cameron. Five other men are also named, though not as rebels: John McArtne, John McGlashan, John McKennith, Alexander Cameron and John McKenzie [4].

In 1727, Alexander Murray of Stanhope carried out a thorough survey of Ardnamurchan. From this we have detailed statistics for the three settlements, of which these are some:

• Swordlechorrach had six families consisting of nine men, nine women and six children. It was valued at five pennies, and had 780 acres of land.

• Swordlemore had five families consisting of ten men, six women and eight children. It was valued at five pennies, and had 1,230 acres of land.

• Swordlecheil had nine families consisting of fourteen men, twelve women and eleven children. It was valued at eight pennies, and had 2,340 acres of land.

Records for 1737 show that the tenant at Swardlechorrach was Archibald McNiven and at Swardlemore was Archibald McDonald; Swordlecheil was shared between five men, Angus McDonald (3d), Arch’d McEacharn (1d), Donald Cameron (1½d), Duncan McLauchlan (1d), and Angus Black (½d).

When, following the ’45 rebellion, William Roy drew his military maps of the Highlands, between 1747 and 1751, the three Swordle settlements were marked but, from the styalised form of each settlement, it is unlikely that their sizes are accurate.

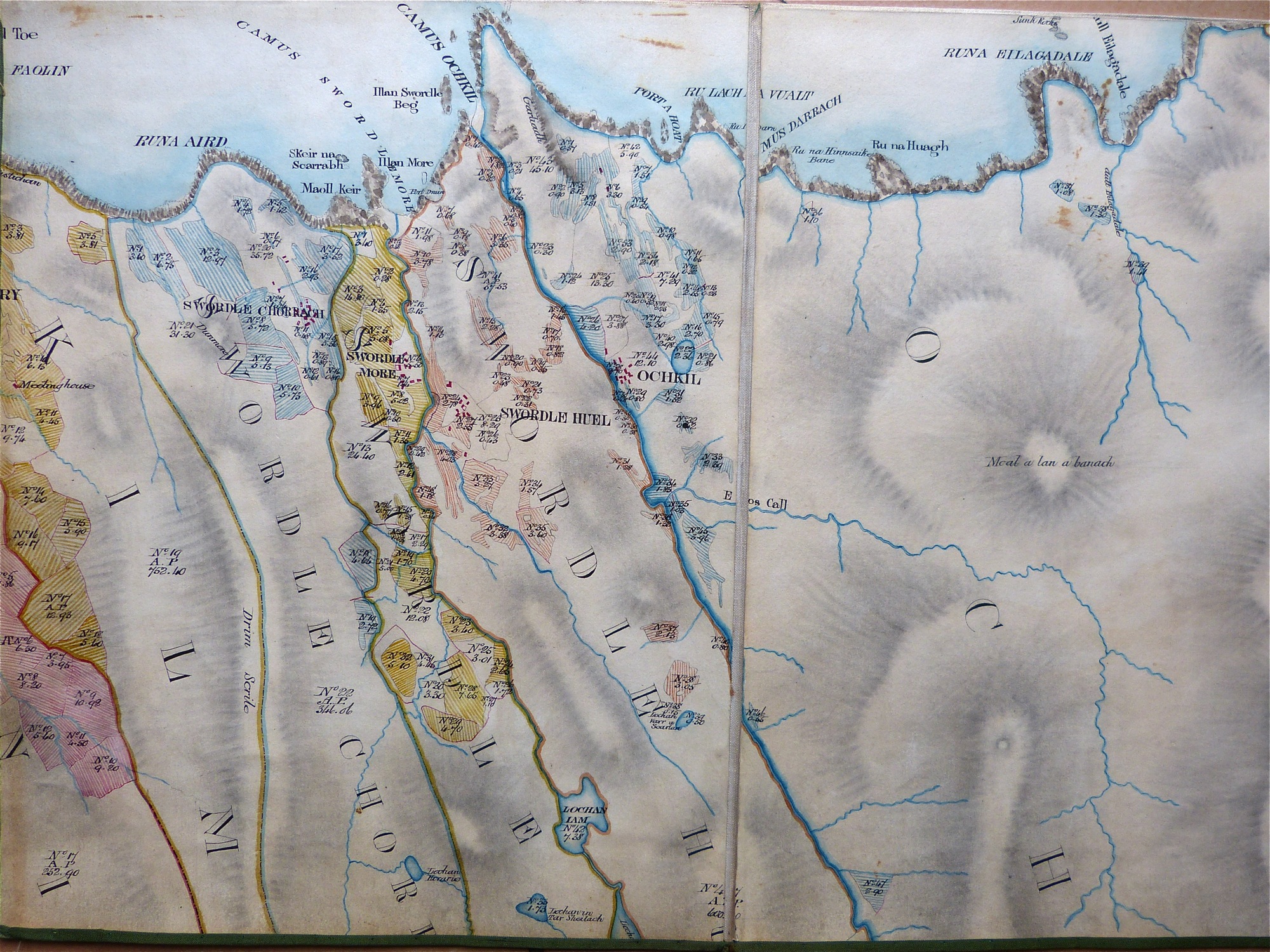

William Bald’s map, drawn in 1806 as part of a survey of the Ardnamurchan Estate, is fascinating as it shows the three settlements five decades before they were destroyed. The original held in the National Library of Scotland is badly faded, the main loss being the red colour which marked the buildings. The map shown is an excerpt from a very good copy of the map, completed in 1856 [5]. The three settlements’ common grazings are elongate, extending as far south as a line running east from Loch Mudle.

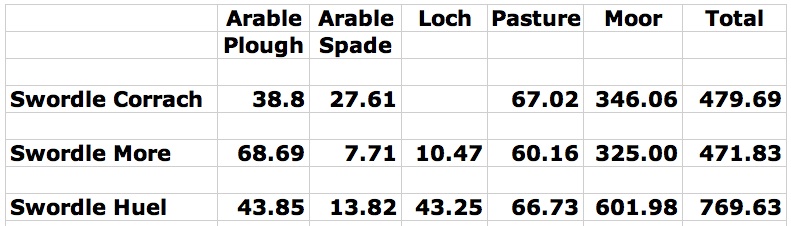

Bald’s survey included totals for the different categories of land in each settlement, as shown in this table, and his work was followed in 1807 by an assessment of each section of the Ardnamurchan Estate carried out by Alexander Low. By this time the owner of the Estate, Sir James Riddell, was under pressure from his accountants to make major changes that would improve his business’ finances. [7]

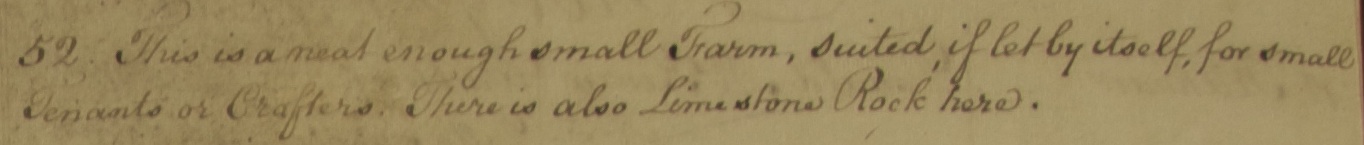

Swordlechorrach:

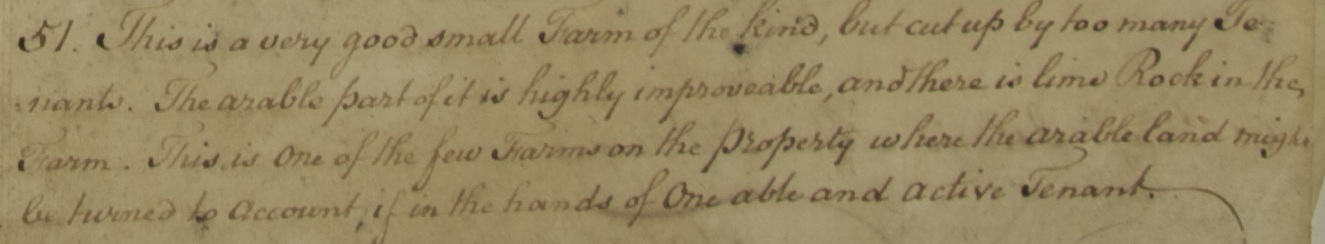

Swordlemore:

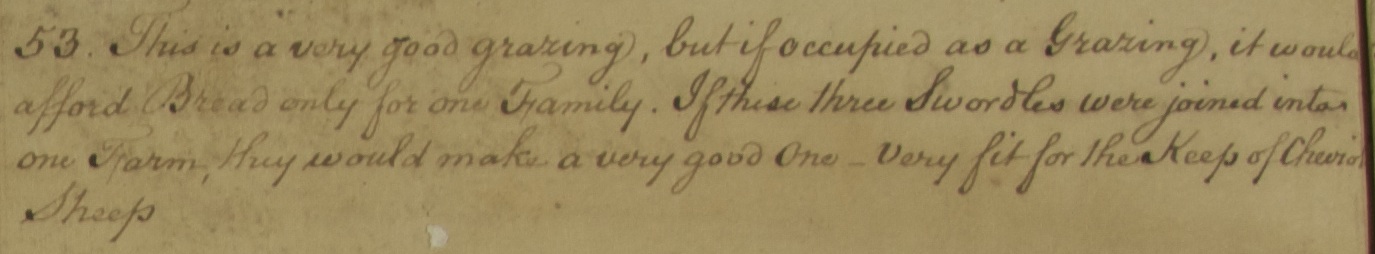

Swordlehuel:

It is clear from Low’s tone that he is considering whether each settlement should be cleared for ‘improvement’, by which was meant consolidating them into packages of land which could be let for sheep farming.

Despite these surveys, Riddell remained reluctant to do much until 1828 when, with the Estate’s finances in increasing trouble, he started clearances on the south side of the peninsula. Riddell also helped some families to leave other settlements by paying their passages if they agreed to emigrate. The Cameron family of Swordle Huel took the opportunity offered, and left from Tobermory in 1837 on board the Brilliant. [9]

Using data from the 1851 report prepared for the trustees of Sir James Riddell’s Ardnamurchan Estate, Robert Curran has found that the three Swordle townships had a total population of 123, including 88 crofters and their families and 35 cottars and their families. He has compiled a spreadsheet which includes the names of the families – here.

The Swordle settlements were finally cleared in 1853. In his ‘History of the Highland Clearances’, dated 1914, Alexander MacKenzie described these clearances, quoting evidence submitted to Deer Forest Commission of 1892 and notes of conversations which he had with actual witnesses of the incidents described. His account is as follows:

“Additional clearances were effected on the Ardnamurchan estate in 1853, when Swordle-chaol, Swordlemhor, and Swordle-chorrach, with an aggregate area of about 3000 acres, were divested of their crofting population, and thrown into a single sheep farm. Swordlechaol was occupied by four tenants, Swordle-mhor by six, and Swordle-chorrach by six. Five years previous to the evictions, all the crofters came under a written obligation to the proprietor to build new dwelling-houses. The walls were to be of stone and lime, 40 ft. long, 17½ ft, wide, and 71 ft. high. The houses, two-gabled, were to have each two rooms and a kitchen, with wooden ceiling and floors, the kitchen alone to be floored with flags. By the end of 1851 all the tenants had faithfully implemented their promise, and the work of building was quite completed. Tradesmen had been employed in every case, and the cost averaged from £45 to £50. When the people were ejected, two years later, they received no compensation whatever for their labours and outlays. They were not even permitted to remove a door, a window, or a fixed cupboard. Some of the houses are still intact in this year of grace, 1914, one being occupied by a shepherd on Swordle farm, and another used as a byre. They compare favourably as regards size, design, and workmanship with the best and most modern crofter houses in the Ardnamurchan district. The Swordle tenants were among the best-to-do on the Estate, and not one of them owed the proprietor a shilling in the way of arrears of rent. When cast adrift, the majority of them were assigned “holdings” of one acre or so in the rough lands of Sanna and Portuairk, where they had to start to reclaim peatbogs and to build for themselves houses and steadings. Sir James Miles Riddell was the proprietor responsible for clearing the Swordles.” [6]

MacKenzie’s statement that ‘not one of them owed the proprietor a shilling in the way of arrears of rent’ does not stand up to scruptiny. These clearances followed a report by Thomas Goldie Dickson acting for the Trustees of Riddell’s Estate, which stated that, in 1851, the Swordle tenants owed over £400 in rent arrears.

We now know the name of the factor who carried out the clearances on behalf of the estate and its trustees. Robert Curran, researching the story of Mary Ann Henderson and her family’s eviction from Swordlechorrach writes, “Mary Ann’s account of the evictions ended with, ‘The name of the factor who was the agent of these tyrannies and inhumanities was Ramage.'” Robert continues, “You can just feel the suppressed anger in this, so I decided to have a go at identifying the man. There was nothing in the census of 1851 but in 1861 a John Ramage appears as a farmer employing three lab(ourers) and two girls living with his family at Swordlemore. He is an outsider, born in Lanark. My guess is that he’s the man, as he’s the only Ramage in the census for Western Ardnamurchan. I wonder if his lease included an obligation to clear the properties?

“The 1861 census shows show the impact of the clearance on the population. AS recorded above, in 1851 there 123 people living at Swordle; the 1861 census records just 8 men and 17 women. At Swordlechaol, three houses were occupied, one by 85-year old wool shearer John McPhail, his wife Janet and a grand-daughter. A second housed Mary Stewart and Jane McPhee, dairymaid and domestic servant respectively but both designated as paupers. In the third lived widow Anne McColl and her sister Catharine.

“There was only one occupied house at Swordlemore with ten occupants, headed by farmer John Ramage, his wife Mary, a daughter and a son. The others were a retired farmer who was boarding with the family, a male visitor, two male farm servants and two female domestic servants.

“At Swordlechorach there were three houses. One was occupied by shepherd Matthew Morrison, his wife Jane and two young daughters. In the second lived Catharine McKay, a widow designated as a pauper, and an unmarried female boarder. The third housed Isabella McPhee, a domestic servant, and her daughter.” [10]

The destruction of the settlements here was so thorough that, unlike earlier cleared settlements like Bourblaige, so little was left of the buildings that they are almost invisible today except to the trained eye. The archaeologists of the Transitions Project have carried out excavations of Swordle Corrach (above) and, more recently, of Swordle Huel, and have found much to support the grim stories of their clearances.

The census of 1891 shows the effect on the population of the area: the whole Swordle area then had only six families totalling twenty-two people.

When the Ardnamurchan Estate was broken into ‘lots’ for sale in 1948, while the Swordle lot was marked on the map included in the sale brochure, it never came up for auction, having already been sold – as can be seen from the word ‘SOLD’ scrawled across this copy of the map, held by Ardnamurchan Estate. Note that the southern, common grazings area of the original three settlements, which stretched down as far as Loch Mudle, has been removed from the new farm. [8]

Swordle remained in private hands until a few years ago, when it was re-acquired by the Ardnamurchan Estate.

[1] Ardnamurchan Place Names, Donald MacDiarmid, ‘Celtic Review’, 1915.

[2] J E Kirby (2015) ‘The Lost Place-names of Ardnamurchan and Moidart’ – available from Amazon

[3] ‘A Plan of Loch Sunart, Alexander Bruce, 1706, in the National Library of Scotland.

[4] Inhabitants of the Inner Isles, Morvern and Ardnamurchan, 1716, ed Nichloas Maclean-Bristol, Edinburgh, 1998

[5] Bald’s map of 1856, courtesy Donald Houston of Ardnamurchan Estate.

[6] ElectricScotland – here

[7] Both Bald and Low’s papers and maps are held in the National Library of Scotland.

[8] 1948 sale brochure, courtesy Donald Houston of Ardnamurchan Estate.

[9] Brett Cameron of Newcastle, Australia – personal communication.

[10] Robert Curran, New South Wales, personal communications. Robert’s website, with the story of Mary Ann Henderson, is here.