The settlement of Sanna lies near to Great Britain’s most westerly point. This picture of the township shows that it is divided into a northern group of dwellings, Lower Sanna, centre distance, and a more dispersed southern group, Upper Sanna. In the foreground can be seen the ruins of buildings erected in the mid-nineteenth century when large numbers of people were moved here from communities cleared from Ardnamurchan Estate.

The machair, the shell-sand area that lies between the village and the sea, was home to groups of Bronze Age people (2,800 – 1,800 BC) who camped near the beach and enjoyed the abundant shellfish. A paper by T C Lethbridge published in 1927 by the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland describes two layers of human activity exposed in the dunes, each of them continuous for some hundred yards. In the upper layer he found a bronze broach and a pin which he dated to the 8th or 9th century. He found two areas if interest in the lower. One he describes as a midden, a rubbish dump, containing pieces of Bronze Age pottery made by Beaker people, flint knives, axe heads, and a barbed arrow head. Not far away, he found another midden, but this also showed signs that it might have been a cremation site, consisting of burn bones surrounded by pebbles the size of oranges. Some of the artifacts are in the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Cambridge. Further finds have been made by others – for example, arrow heads, borers and and scrapers were found by R Crerar, and reported in a paper in 1961.

Lethbridge’s broach and pin are good evidence of occupation in the first millennium AD, and the Vikings must also have known Sanna and used its beaches, though the only recorded evidence is the name itself, which is derive from the Norse words sandr, sand, and ey, an island. [1]

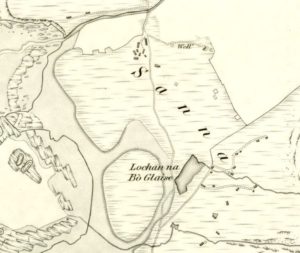

Sanna is not shown in any of the early maps, nor does it appear in Alexander Murray’s 1737 survey of Ardnamurchan, but when William Roy made his military map in the 1750s (above), the village of ‘Sand’ is clearly marked. For its time, Roy’s map was an incredible achievement, but it is far from accurate. For example, the number of red marks does not necessarily indicate the number of buildings. The Sanna Burn is shown as reaching the sea near the now-ruined village of Plocaig. Either Roy was mistaken or, as Bob Jones from Suffolk has suggested, this might have been the original course of the Sanna Burn, which was later diverted, either by man or naturally. Roy’s positioning of the Sanna houses suggest they were on a site which today would have been beside the burn, with the worked land in the flat area to the south of them. [2]

Roy’s record of the amount of worked land would suggest several inhabitants in 1747, but the Kirk Session of Ardnamurchan Parish in 1779 record only one inhabitant at Sanna [4], Archibald MacArthur, a shepherd. Bald’s superb map of 1806, A Plan of Ardnamurchan and Sunart, above, [3], marks Sanna as ‘Saune’, and calls the Sanna Burn ‘Avhin Saune’, Sanna River. Despite the extent of the worked land, only one building is marked. Sanna, at that time, was part of the settlement of Achosnich.

The first Scottish census in 1841 lists 18 families in Achosnich. It may be that there were no permanent residents in Sanna, the land being tended by farmers from either Achosnich or Achnaha. However, in Thomas Goldie Dickson’s report to the then landlord of Ardnamurchan, James Milles Riddell, dated 1851, he lists 21 tenants in Sanna, many of them cleared with their families from the three Swordle settlements approximately fourteen miles away along the north coast.

The OS 6″ map, surveyed in 1872, shows that the township was extensive, with the main track out of Sanna still running south to Achosnich rather than to Achnaha, as it does today. It also shows a lochan, Lochan na Bo Glaise, just to the west of where the present car park stands, though this was probably shallow and seasonal. The well which is marked in Lower Sanna still exists today. [2]

The 1881 census shows a considerable increase in population. Included in this census was the population of Plocaig a small now derelict row of houses a quarter of a mile east, giving some 22 houses and 85 people in total. Many of the heads of households are listed as women and there is a distinct lack of work age men, probably because, to survive on these tiny crofts, the men would have gone away, typically to sea, or to the police force in Glasgow. [4]

Some time in the 1890s the small mission hall was built – it’s seen at bottom left in the photograph at the top of this entry. It had no denomination and was used alternately by the Church of Scotland and the Free Church, indicating that the Sanna people attending worship must have been of split between the denominations. It is still used today.

By the early 20th century, the people of Sanna were campaigning for a road to connect their village to the paved road which had, by now, reached Achnaha. MEM Donaldson, who later built Sanna Bheag, the large house at the southern end of the settlement, describes in her Further Wanderings – Mainly in Argyll (1926) the battle the crofters had to get their road built. With many of the men away, ‘mostly in the merchant service’, all goods for the village, such as fuel, building materials and other provisions, had to be carried in from Achnaha on the women’s backs. Worse, she describes the hardships of having to carry a coffin along the track to Achnaha, as all burials took place in Kilchoan. By 1925 the road had been built, but the story suggests that, a couple of decades previously, Sanna was already connected more to Achnaha than Achosnich.

MEM Donaldson goes on to describe the village as having twenty houses built of stone with reed thatched roofs, of which one ‘is over a hundred years old’. The older cottages were of the ‘but and ben’ type, and some still had floors of beaten earth. However, all by now had chimneys, made of cones of thatch, but their water came from the nearest burn. The crofters paid an average of £1 12s and 6d a year to the landlord for their land, but this also gave them a share of the common grazing on which they could graze ‘two cows and their followers’. The grazings was overseen by a committee of three crofters, elected every three years. She noted that, ‘There are only cows at Sanna, and horses and sheep are not allowed’. The crofters also kept chickens, grew potatoes and ‘corn’, and caught fish.

Sanna today has six crofts, reorganised from the many small crofts of Riddell’s time, and, in 2016, a permanent population of eight, most of the houses being holiday cottages. However, the township is a tourist attraction, renowned for its white sand beaches.

[1] Donald MacDiarmid – Ardnamurchan Place Names [2] National Library of Scotland maps – here. [3] Courtesy Ardnamurchan Estate [4] Courtesy Sue Cheadle