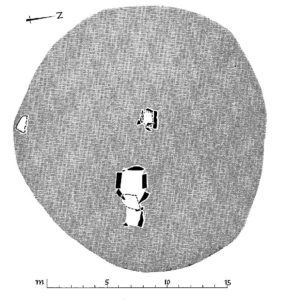

Ormsaigmore looks south onto Kilchoan Bay, a shallow bay with a small, protected beach. Some 6,000 years ago, the protected landing place, and the relatively good soils of the land behind it, attracted Neolithic settlers. No trace of their occupation remains except for a chambered cairn, Greadal Fhinn, which stands on a knoll 300m back from the beach. The remains of the cairn are roughly circular, with a diameter of approximately 20 metres. The cairn mound may originally have been formed of loose rocks, but these have since been removed, probably to use as building materials, exposing the two burial chambers.

At the centre is a cist grave (left in the picture), with a passage grave in the southeast quadrant. The cist grave is rectangular in plan, and formed of four upright slabs covered by a cap stone which has slipped. The entrance may have been through a narrow gap in the southeast corner. The chamber of the passage grave is formed of five uprights and one remaining cap stone, while the passage is formed of two vertical slabs. There were more slabs but they, along with the rocks that formed the cairn, have been taken as building materials.

This plan of the cairn is taken from Ritchie’s paper on his excavation of a similar cairn at Achnacreebeag, near Oban – link here. It too has both cist and passage graves, the latter also opening southeastwards. From the artefacts found, Ritchie was able to date the structure but was not able to suggest whether the two chambers were built at the same or different times. They are part of a family of many cairns, of varying design, in the Lochaber and north Argyll area.

It seems likely that the Ormsaigmore cairn was surrounded by a number of kerb stones. A large, recumbent stone on the south side may be one of these.

The knoll isn’t high, yet its location at the centre of the farming land means that it dominates the inhabited area, visible both across the worked land of Ormsaigmore and to boats passing in the Sound of Mull.

Confusingly, the cairn is known as Greadal Fhinn. Local lore has it that the ‘Fhinn’ refers to a Viking chieftain Keitell Flatnefr of Raumsal, and that he was buried here. This Viking was known on the west coast as Caithil Fin. In 888AD he fled Norway and, according to the Sagas, settled on the west coast of Scotland, where he later died.

Further evidence that the area was settled in Viking times comes from the name: Ormsaigmore is derived from the Norse words ‘ormr’, a snake, and ‘vik’, a bay, the word ‘more’ being Gaelic. As the Vikings well appreciated, the Ardnamurchan Peninsula holds a pivotal position astride the sea route along the Scottish West Coast. Ormsaigmore’s bay, as the most westerly anchorage on Ardnamurchan’s south coast, is very likely to have supported the same sort of Viking settlement as must have existed around the Viking boat burial at Swordle on the north coast. Yet the Ormsaigmore Vikings, as in so many of the areas they settled, left no long-lasting legacy except in place names.

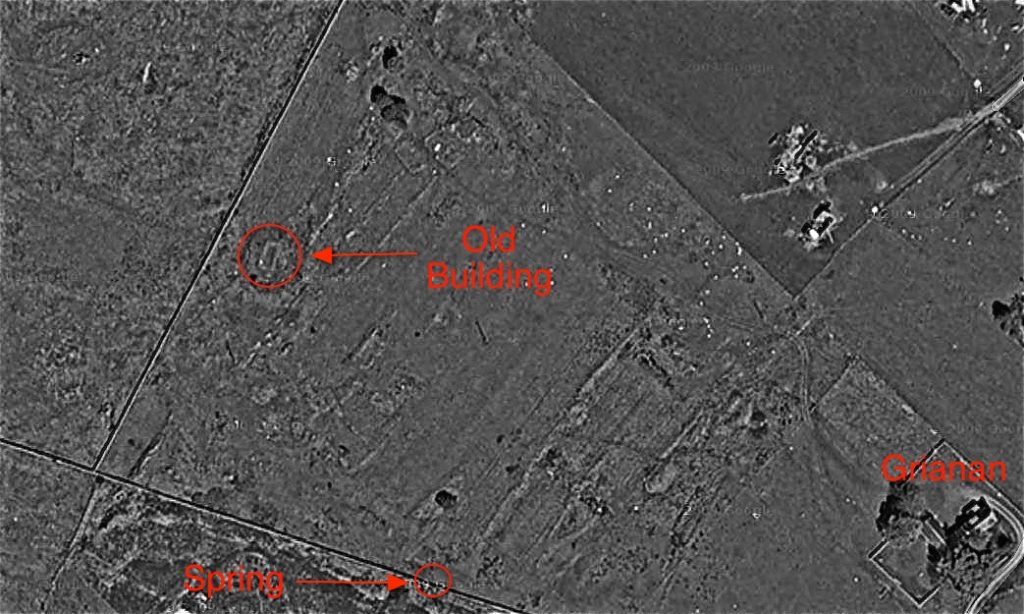

In subsequent years, a settlement existed on the Ormsaigmore site, the remains of which are easily found in the field between Greadal Fhinn and the farm house, Grianan. We know that its population in 1716 was seven men over the age of 16. Alexander Murray’s survey of Ardnamurchan in 1737 found that it had a population of 29, grouped in six families comprising nine men, eight women and twelve children. The total area of the ‘tenement’ was 984 acres, and the ‘penny land’, a valuation of the productivity of the land for rent purposes, was stated as 4. The pasture supported 48 cows, 12 horses and 48 sheep.

This map, drawn by William Roy between 1747 and 1755 [2], shows the location of Ormsaigmore settlement (arrowed), along with the neighbouring settlement of Ormsaigbeg – though the name ‘Ormsaigbeg’ is in the wrong place.

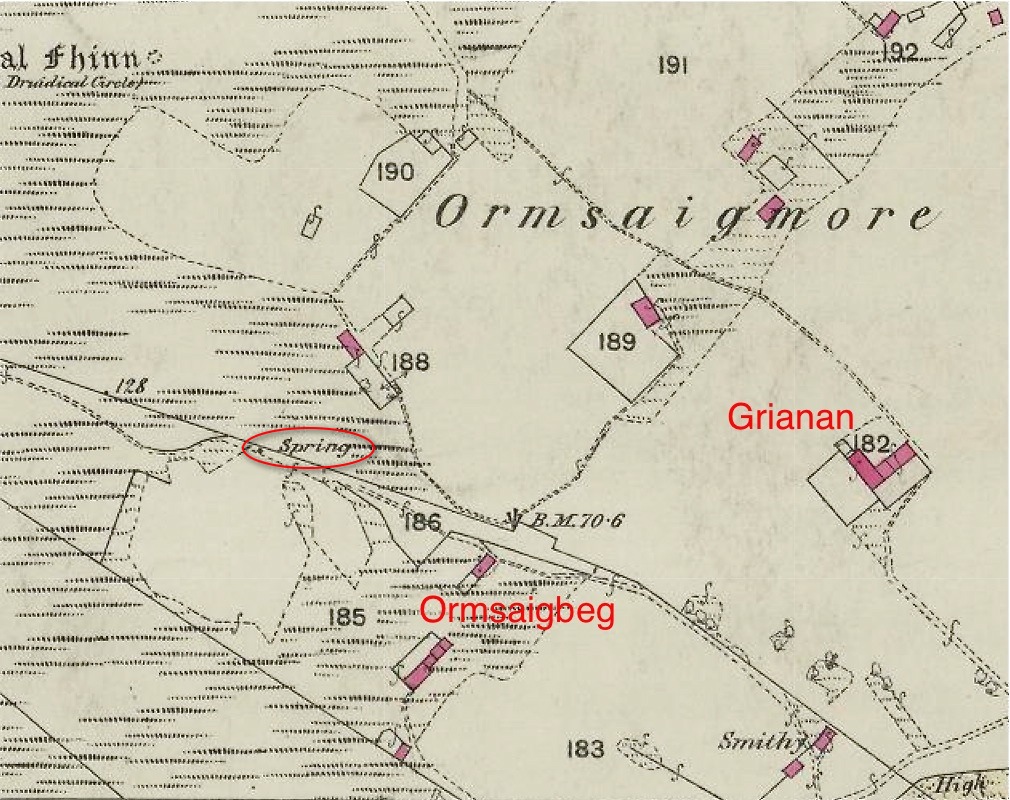

William Bald’s map of 1806 [3] shows the settlement in such detail that 12 buildings can be distinguished, along with two enclosures. Five buildings are marked in the wall which separated it from Ormsaigbeg – it’s not clear to which settlement they belonged. The houses were built on the poorest agricultural land, in places where the hard rock protrudes. Between these are small areas of flat land, like terraces, which were cultivated.

Bald’s map shows very clearly that the better agricultural land around the village was divided into four large runrigs, which are still visible on the ground. Other areas of less easily worked land, articularly on slopes, show clear sign of lazy beds. Some of these lazy beds extend upwards onto the lower slopes of Tom na Moine to the northwest, land which has now been overtaken by heather. These suggest that there were times when the population of the settlement grew beyond the capacity of the main fields to support it. The answer was to expand onto marginal land: this says something about the society’s limited ability to innovate in response to crisis.

The OS 6” map of 1872 [2] shows a radically changed landscape. The buildings of the settlement have largely disappeared, cleared to make way for a single, large sheep run. This clearance, by Ardnamurchan Estate, the landlord, took place around 1832.

The new sheep farm covered the whole of the old settlement’s land. The amount of ‘improved’ land was reduced, and the sheep would have been run on the runrig and common land in the hills to the northwest as well as within Ormsaigmore itself. With the exception of building 182, Grianan, which was the farmer’s house, all the roofed structures (in pink) were farm buildings such as byres or cottars’ dwellings. Note that Greadal Fhinn is referred to as a ‘Druidical Circle’.

By contrast, the clearance of neighbouring Ormsaigbeg resulted in its present-day organisation of small crofts on narrow, individually-worked strips of land running from the common grazings at the back to the foreshore. Some of the inhabitants of the Ormsaigmore settlement were moved to Ormsaigbeg.

The farmer’s house, Grianan, now demolished, reflected the spirit of the improvers who made these drastic changes to the West Highland landscape. It’s a solid, substantial house with associated large barns. These match the confident, straight walls which cut across previous agricultural features such as the old runrigs. Yet in one way it conforms: it is built on the poorer agricultural land.

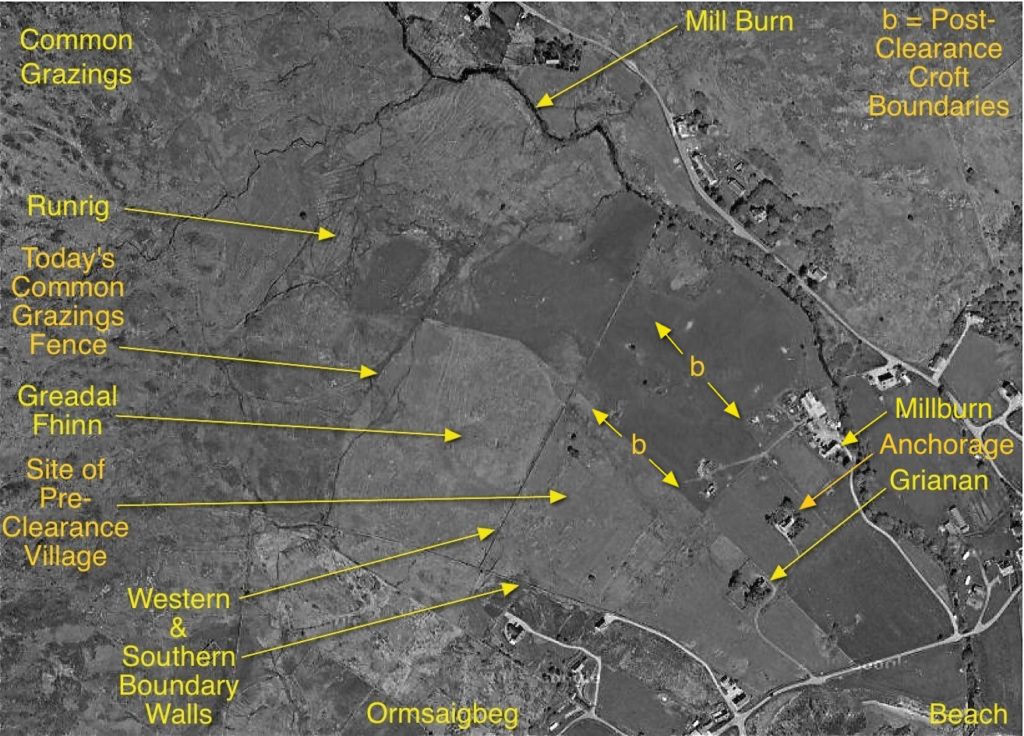

This shows the area today. Following the Crofters’ Holdings Act of 1886, Grianan farm was divided into three crofts – Grianan, Anchorage and Millburn. This did not take place until just before the First World War. Millburn croft house was built in 1922. The boundaries of the crofts are marked with the letter ‘b’. By comparison with the crofts in Ormsaigbeg, these are reasonably large, and include some good land.

It is important to note that the present-day buildings occupy the area of the old settlement, and that the most intensively-cultivated land remains the same as the best runrig fields. In some respects, little, over the last 6,000 years, has changed.

References:

[1] Lost Place-Names of Ardnamurchan – Jim Kirby – available from Amazon [2] Maps available at the National Library of Scotland’s website here. [3] William Bald’s ‘Plan of Ardnamurchan and Sunart, Argyll’, 1806, courtesy Ardnamurchan Estate.