Ormsaigbeg is a separate crofting township within the general geographic area which is referred to as Kilchoan. The settled land today, as shown on this map [1], extends southwestwards from the stone wall which runs inland on the south side of Grianan croft, to the end of the Ormsaigbeg road at Cuingleum.

Ormsaigbeg’s early history is largely lost. Evidence that it was settled by the Vikings when they dominated this coast over a thousand years ago is suggested by the settlement’s name, which is derived from the Norse ormr, a snake or serpent, and vik, a bay, with the Gaelic word bheag, small, added [2].

One imagines that, at least from the Middle Ages onwards, it was a typical settlement, with a small group of houses, more or less huddled together, surrounded by infield land which was used intensively for arable farming, surrounded again by outfield land which, if it was used for arable farming, had to be left fallow for long periods. The settlement also had a very extensive area of common land, now called the ‘common grazings’, which ran north and westwards into the hills.

Ormsaigbeg’s land was valued at 20/- in 1667. Alexander Murray’s survey in 1727 found that there were six families comprising eight men, ten women and ten children, a total population of 28. The land consisted of 1,640 acres, and the ‘penny land’, which was an assessment of land productivity for the purposes of levying rent, being 5. There were 60 cows, 16 horses and 60 sheep.

In 1737 it had five tenants, Neil Campbell, Alexander MacDonald, Donald McIllvraw, Hugh Henderson and Kenneth McKenzie. In the same document, the settlement is associated with another settlement or shieling at Reidh-Dhail, which is marked on current OS maps some 2 kilometres to the west of Ormsaigbeg. [3]

The first map evidence comes from Bruce’s map of 1733, left, [4], which shows a settlement of ‘Ormsaigleg’, as well as neighbouring settlements of Ormsaigmore and a much bigger, ‘Killehoun’. On this map the settlement is shown about 100m inland from the coast.

The first map evidence comes from Bruce’s map of 1733, left, [4], which shows a settlement of ‘Ormsaigleg’, as well as neighbouring settlements of Ormsaigmore and a much bigger, ‘Killehoun’. On this map the settlement is shown about 100m inland from the coast.

Roy’s military map, dated some time after around 1750, right, [4] marks ‘Ormsaig beg’ much further to the southwest, beyond the extremity of the present settlement, and on high land. However, it also marks another, un-named settlement in almost exactly the position Bruce marked his ‘Ormsaigleg’, though Roy seems to have lumped this in with ‘Ormsaigmor’.

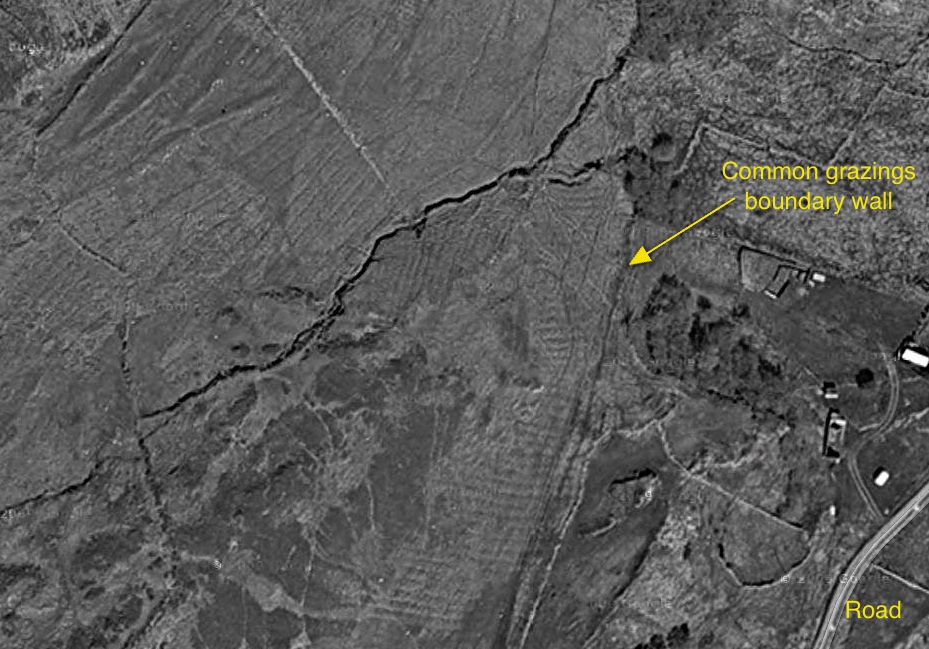

There is plenty of evidence, both on the ground and from above, that a settlement existed where Roy marked his Ormsaig beg’. This Google image shows an area to the northwest of the end of the Ormsaigbeg road. Extensive field workings are visible, including lazy beds and field boundaries, on what is now part of the present township’s common grazing.

Bald’s map of 1806 [5] is much more detailed than Roy’s. It places Ormsaigbeg back where Bruce originally had it, and shows that it consisted of about a dozen buildings. The map is good enough to locate the original settlement fairly accurately, using the position of the little lochan by the sea – just by the Ferry Stores, and now called Lochan nan Al – and the small burn which ran down through the settlement.

This stream, and the slight turn it makes, is easily found today, and is seen on this enhanced Google image, but neither here….

….nor on the ground – the area occupied by the settlement was roughly within the red oval on this photo – is there much evidence of its buildings, most of which were probably destroyed and their stones re-used to make field walls and new houses.

On Bald’s map there is no sign to the southwest of the ‘satellite’ settlement marked on Roy’s map, although it shows fields still being worked in that area. Since Bald was meticulous in marking every building, it seems likely that, by 1806, this settlement had been abandoned.

Bald’s map is remarkable for its detail. It shows clearly the separate fields belonging to the settlement, gives the area of each, and marks the limits of the common grazing, which extends inland and to the west – follow the reference at the bottom of this entry to see this.

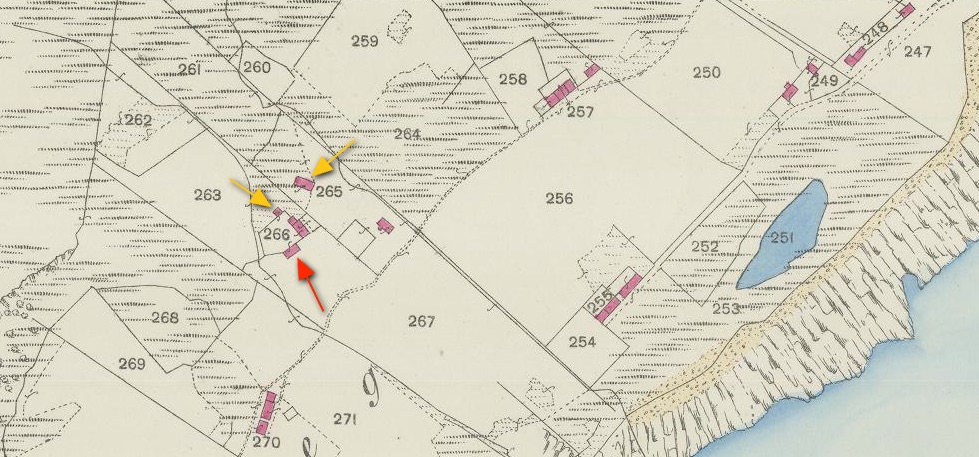

The present layout of Ormsaigbeg was largely established by the time the Ordnance Survey drew its first map of the area in 1872 [4]. The settlement had gone, its communal landholding arrangement replaced by separate crofts, each of which ran from the common grazings wall at the back down to the sea. This map clipping, taken from the 1872 OS 25″ map [6], shows the croft on which the settlement once stood. The building marked with a red arrow is the present croft house, so the others around it may have been structures left from the settlement, used as byres and store-buildings. Of these, only the two marked with yellow arrows are visible on the ground today; one is still in use.

The drastic changes visible in the 1872 map came as the result of Sir James Riddell’s policy of ‘improving’ his Ardnamurchan Estate by clearing some settlements and turning their land over to tenant sheep farmers. Their inhabitants, and those of settlements which were not to be used for sheep, were resettled on individual, tenanted plots called ‘crofts’. This was a process which was happening all over the Highlands and Islands, and is generally known as The Clearances. Many people, rather than face resettlement on plots of land far too small to support a family, left for newly industrialised Scottish cities such as Glasgow, or for overseas destinations such as Canada and New Zealand.

For those that remained in Ormsaigbeg, life must have been exceptionally hard. The crofting system was designed to force people who had been subsistence farmers to work for cash. In some parts of the Highlands money could be earned by collecting kelp for the phosphate industry, but on Ardnamurchan it meant that the men were obliged either to find work on the Estate, in other local industries such as salmon fishing, or to enter occupations, such as the merchant navy, which took them away from their families.

Only the land close to the sea was fit for growing crops. Since the staple was potatoes, crofters were even harder hit when potato blight arrived in the Highlands in the 1840s. At least Ormsaigbeg crofters all had access to the sea, which meant that they could collect shellfish and, since all had boats, go out into the Sound of Mull to fish. Most crofts also had a cow which provided milk, and sheep which were largely kept on the common grazings. A description of this life is contained in Mary MacGillivray’s booklet, ‘Growing Up on an Ardnamurchan Croft’, available locally.

[1] Bing Maps [2] Ardnamurchan Place Names by Donald MacDiarmid [3] Jim Kirby ‘Lost Place-Namess of Ardnamurchan, available at Amazon [4] National Library of Scotland, maps – here. [5] Courtesy Ardnamurchan Estate